- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

1858-1861 Brattleboro, Vermont

1862-1866 Orange, Massachusetts

1866-1876 White Mfg. Co. Cleveland, Ohio

Since 1876 White Sewing Machine Company

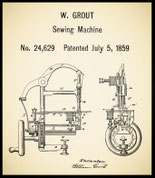

Thomas Howard White, being mechanically skillful and naturally ambitious, devoted every moment he could find to experimenting with strange machines. It was the age of inventions and one of the most fascinating devices that had been brought out was a machine for sewing. He experimented patiently with this promising device and in 1857 invented a small hand-power sewing machine of his own, on which he (?) obtained patent in 1859.

In 1858 Thomas Howard White, with a capital of $350 and with William Grout, who acted as salesman, as a partner, began manufacturing sewing machines in Templeton.

notes:

Samuel Barker and Thomas White, Brattleboro, Vermont 1858-1861

The Brattleboro sewing machine produced by Samuel Barker and Thomas White was a patented single-thread family machine.

"The New England" was the name of this machine, the retail price of which was ten dollars and although the partnership with Grout lasted only a year, the business prospered and

in 1863 the demand had grown to such an extent that White moved to a larger factory at Orange, Massaschuttes, where he manufactured for three years.

In 1866, White removed to Cleveland, Ohio, taking with him a few of his best mechanics and there founded the White Manufacturing Company.

For ten years the new factory built sewing machine heads for W. G. Wilson, until that company purchased the existing patterns, templets, special equipment and established an independent plant in Chicago.

1873

Notice is hereby given, that the petition of George Haseltine, of the International Patent Office, Southampton-buildings, London, Doctor of Laws, praying for letters patent for the invention of "an improved lamp".

A communication to him from abroad by Thomas Howard White and Edgar Knight, both of Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. of America, Manufacturers, was deposited and recorded in the Office of the Commissioners, on March 5, 1873 and a complete specification accompanying such petition was at the same time filed in the said Office.

1876 THE BEGINNING

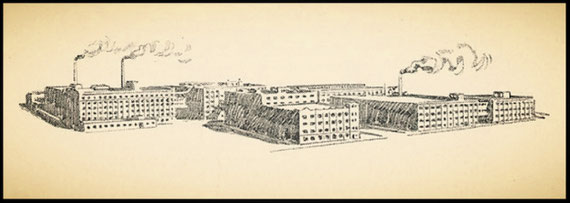

In 1876 when most the "Combination" patents had expired, two employees D'Arcy Porter and George W. Baker developed a new machine which became the company's flagship product. The Company with 600 employees, was incorporated and took the name of White Sewing Machine Co.. The new sewing machine originally was named the "White SMC", only later taking the name "White".

An extensive organization of branch dealers was established in the United States and following the opening of a London office in 1880, the company's foreign trade grew rapidly.

In 1883 an improved version of the "White Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machine" was introduced.

In 1884 the White company had 500.000 machines in use.

In the late 1890s the company's vibrating-shuttle model was supplemented with a new rotary model, known initially as the "White Family Rotary". It became the most popular White model and continued to be manufactured by the company in various incarnations into the 1950s.

In 1901, the company produced its first automobile. Thomas White, still president of the company, gave control of vehicle production to his three sons, Windsor, Rollin and Walter.

In 1902 the company produced "One Million 500.000" sewing machines.

While the founder's love was truly sewing machines and he pursued many related innovations, his sons became interested in other types of machinery, such as steam-powered automobiles. The early days of the 20th century were explosive with growth for the company. Indeed, White diversified as early as 1903, making roller skates, automatic lathes, kerosene lamps and even cars.

When White's sons couldn't convince their father that the steam automobile was worth keeping in production, Windsor and Walter White spun that product division off from White, forming the White Motor Corporation in 1906.

The White Sewing Machine Co. then turned its attention back to its original product.

In 1909, White Motor Corporation introduced a gasoline-powered automobile.

In 1910, White Motor Corporation produced its first gasoline- powered truck.

In 1916 White bought the Raymond Manufacturing Company based in Canada

Meanwhile, White's sewing machine innovations piled up, including the progenitor to the portable sewing machine, the first furniture-style sewing machine cabinets, the first full rotary mechanism and, in the 1920s, an electric motor.

It was in 1918 that the company dropped the passenger car line and very successfully specialized in producing trucks and buses.

" It was about 1876 that the White Sewing Machine Company manufactured its first sewing machine. The industry was started and was owned by the late Mr. Thomas H. White. Since that year, in a total of four decades, this company has manufactured and sold approximately 4.000.000 sewing machines. There was a very small output in 1876, but the business was continuously and consistently developed by Mr. White and his associates. In recent years they have manufactured and sold approximately 600 machines a day. Practically 80 per cent of this modern production are White rotaries."

1918 - A History of Cleveland and Its Environs

Naturally, all of these advances made the company's sewing machines even more popular, so in 1923, White Sewing stopped manufacturing its other product lines and focused on sewing machines and accessories.

Like many other sewing-machine manufacturers, White manufactured and labeled many for retailers.

In 1924 after acquiring the Domestic Sewing Machine Company of Buffalo, New York, the company signed a contract with Sears, Roebuck & Co to supply them with private-label machines. The White company continued manufacturing the Domestic-made Franklin sewing machines for Sears Roebuck & Co. Domestic became a fully-owned subsidiary of White. Over the next 12 years, White supplied Sears with about 20 percent of their sewing machine output.

By 1926, White had acquired Theodore Kundtz Furniture Factory, which made White's sewing furniture, King Sewing Machine Co. and, from Sears, the Domestic Sewing Machine Co. (1924). Under the leadership of company president A S Rodgers, the company was reorganised as the White Sewing Machine Corporation. Eventually a subsidiary, which became known as Standard Sewing Equipment Corporation, was formed.

With the Great Depression came renewed interest in home sewing. White continued to innovate, introducing the first sewing machine outside of its traditional black models, which was made of a magnesium alloy and was also much lighter than its forebears.

This product did well enough to warrant the formation of a second subsidiary in 1939, White Sewing Machine Products Limited, in Canada.

During World War II, like many U.S. companies, White turned over its manufacturing for the purpose of producing goods to aid the war effort. Production was high enough to necessitate a move to a bigger plant in 1949. A new administration building was completed in 1951.

The world was a changed place by then, as a strong demand for consumer goods ensued. While White had improved its production methods significantly, and 2,000 machines were rolling forth a day, imported machines from Germany, Italy, and Japan, had begun to swamp the U.S. market, and it was becoming impossible to compete with their prices. In fact, White spent on materials alone what a finished, imported sewing machine cost in the United States. Even though the company had a hearty $20 million in sales in 1954, it reported a $440,667 net loss and had been on an earning slide for the past six years. In such a changing industry, and world, White could no longer afford to remain a one-product company. When Sears, which represented 40 percent of White's business in the early 1950s, gave its manufacturing contract to the Japanese, the company fully realized the need to diversify.

Enter Edward Reddig, an accountant who, upon becoming White's president in 1955, led the charge with a single-mindedness that bordered on ruthless, according to many. Reddig quickly arranged to have White's machines manufactured overseas, to company specifications, and began slashing costs back home, a program that included firing one-third of White's work force.

Reddig also launched an intensive acquisition campaign. The plan was diversity and the targets were largely appliance concerns. White merged with or acquired roughly 14 companies in 1960 alone.

By 1960, White had merged with Husqvarna Viking.

By 1964, the parent company had changed its name to White Consolidated Industries, or WCI, a reflection of its rainbow of acquisitions, which included: the Kelvinator Appliance Division, from American Motors; Gibson, which was then Westinghouse's appliance division; and Franklin Appliance Division of Studebaker. Reddig's recipe was to target companies that were sickly, but not terminal; pay bargain-basement prices for them and then slash overhead, excess product lines, and employees until they were lean and profitable.

One of his targets, Franklin, for example, had lost money in 1964 and 1965 and then had turned a pale profit in 1966; this record was typical of the kind of purchase Reddig sought. As an example of his tenacity in reducing costs, 70 percent of Kelvinator's administrative staff was terminated in the first month after takeover. Among newly acquired companies, research and development was often halted and computer operations were often junked.

Reddig attributed his style to his tenure at Arthur Anderson & Co. in Chicago, during the 1930s, where he was assigned to enter big companies and crack the books.

In 1967, WCI acquired Hupp Corporation, a maker of electric appliances, air conditioners and rangers. By the decade's end, WCI had a comprehensive line of tools, valves, household appliances, and machinery. And its sewing machine operations, being handled overseas, were still regarded as the most innovative in the business. White sewing machines introduced the first overlock system designed for a home sewing machine, the first numbered tension dials, and a recessed cutting system.

By 1968, WCI's sales were $830 million; stunning when compared with the $29 million reported in 1963, or even the $172 million from the year before. WCI was operating from four basic divisions: machinery and equipment; valves, controls and instrumentation; sewing and knitting machinery; and industrial supplies. The machinery and equipment group accounted for about 55 percent of WCI's sales in 1967, valves contributed roughly 20 percent of sales, and about 14 percent of sales came from the sewing division.

In early 1970, WCI was approached by its offspring, White Motor Corporation, which proposed a merger. However, the Justice Department soon forced the two to separate, ruling that the resulting company would have had a monopoly, particularly in light of the fact that WCI then owned 30 percent of Allis-Chalmers Mfg. Co. Allis was a competitor with White Motor in several arenas, and had a few years earlier moved for an antitrust injunction to stop WCI from acquiring further stock. The ultimate scraping of that venture cost WCI dearly; it lost $63 million when it divested White Motor Corp.

Another milestone came in 1975, with the purchase of Westinghouse's major appliance business. This division was in the red at the time and pulling on Westinghouse's capital. Despite the fact that the appliance industry was in a slump at this time, Reddig accepting the $700 million acquisition price, since the division would double WCI's appliance business overnight, and add 60 percent to WCI's overall volume. The purchase meant taking more of a punch than was WCI's habit, as the company usually planned one year per company for turnaround. While Kelvinator was coaxed from a $47 million loss in 1947 to breaking even at the end of the next year, Westinghouse would require more work. As more than 60 percent of its business at the time was in manufacturing private label appliances for Sears, Montgomery Ward, and J.C. Penney, among others, WCI welcomed the opportunity to purchase a brand that would help it compete with appliance giants General Electric and Whirlpool.

During this time, White Motor was doing so poorly the Justice Department reversed its opposition to the WCI merger in 1976, arguing that White Motor would fail without it. Then, in a stunning blow, the directors of WCI voted the merger down. After the White Motor merger was voted down in his absence--the board claimed it was unhappy with the proposed financing--Reddig retired from WCI. By 1976, WCI had doubled its sales and earnings within four years, passing the billion dollar mark. Reddig had transformed WCI from a $20 million sewing machine company into a $1.2 billion presence.

Succeeding Reddig was a three-man team, which initially carried on some of Reddig's plans, such as the 1977 acquisition of Sundstrand Corporation's machine-tool business, which had been losing money. Nevertheless, a parting of philosophies was evident in that, besides being no longer a one-man operation, the new team believed in the value of marketing. Part of its plan for turning the new Westinghouse appliance business around was to spend heavily on advertising.

At that point, WCI ranked third in appliances, behind General Electric and Whirlpool, who priced aggressively. Unlike Reddig, the new management at WCI was willing to sell more actively and loosen the reigns on cost in order to compete. Although an engineering staff was established, and WCI stepped up its advertising budget, the company managed to avoid spending as much on ads as its competitors did, since it sold about half its appliances as private-label brands through the mass merchandisers. By the late 1970s, WCI was a big-league manufacturer of major home appliances, but still not a household word. Then, in 1979, WCI purchased General Motor's Frigidaire division for about $120 million; the company's appliance business then boomed, and meant it was closing in on the competition.

WCI bought the American Tool Company in 1980. Between 1975 and 1985, its sales jumped from $1.2 billion to more than $2 billion. In fact, by 1983, WCI was the nation's third largest manufacturer of refrigerators, stoves, and air conditioners. The company's 84 plants were scattered across the continent, each run with basic autonomy. However, while appliances were profitable, sales weren't exploding and machine tools weren't doing well, so WCI's management trio began hunting for a new business to add to the family. In 1983, the company sold its Sarco subsidiary, a textile machinery division, and closed its steel industry equipment unit.

The company focused on three divisions in 1985: home products, which contributed about 76 percent of sales; machine and metal-basting divisions, providing 12.1 percent of sales; and the general industrial and construction equipment division pitching in the rest. The home products division was an umbrella for the widely known Kelvinator, Gibson, Hamilton, Frigidaire, Bendiz, Philco and White-Westinghouse brands. That year, WCI decided to combine the divisions' four major brands into a single operating unit, to be run out of Columbus, Ohio. Prompting this radical move was the fact that the market had suffered decreasing profits and increasing competition for the previous six months, and WCI was pressed to cut costs. Thus, one effective cost-cutter would be to improve the efficiency of its manufacturing.

While tackling this massive change, another dramatic change occurred. AB Electrolux of Sweden, the largest manufacturer of appliances in Europe, needed to widen its place in the U.S. market. WCI seemed the perfect ambassador. Electrolux approached WCI in 1986, with what was then a very fair offer. After some minor disagreement, the merger took place. Electrolux at that time had sales of $4.6 billion, and its only other holding in the United States was Tappan, a maker of ranges and microwaves, acquired in 1979.

After the takeover, WCI was subjected to a bit of its own medicine, as the company was trimmed and unified, and made more efficient. Underutilized plants were boarded up and product lines were enhanced, in a shift from the no-frills philosophy instilled by Reddig. Electrolux had become the world's largest maker of major appliances, with $9 billion in sales by 1987. Having been cash-strapped just before the transaction, WCI benefited from the financial resources of its new parent.

WCI was soon able to acquire Design & Manufacturing's (D&M) dishwasher business, begin building a new highly modern refrigerator plant, and hire a new head for its marketing sector. It also worked on reducing its distribution costs, a real killer in the industry. The sizable D&M deal alone gave WCI a quarter of the country's dishwasher business, making it second only to General Electric. WCI was fortunate to have such a wealthy parent at a time when so many costly changes were needed; working on brand-name recognition alone cost a fortune. WCI had long staked its fortunes on look-alike models for private labels, which kept costs down; to suddenly invert this strategy and develop distinct products readily recognized and popular with the public was a big change. In the early and mid-1990s, home appliances and products continued to WCI's largest sector. Although little information on WCI was made available after the Electrolux acquisition, judging by Eletrolux's continued growth and health, White was surely thriving as well.

sources:

White Consolidated Industries Inc. History

The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (1931/vol.21)

As reproduction of historical artifacts, this works may contain errors of spelling and/or missing words and/or missing pages, poor pictures, etc.