- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

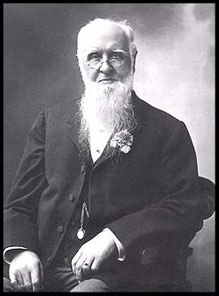

Joseph Harris

Joseph was the son of Thomas Harris, a grocer of Cheapside, Birmingham. Thomas had married Miss Martha Hill at Edgbaston on 16th September 1830, and Joseph was born on 25th December the following year.

When Joseph was 14, he was indentured as an apprentice to George Briggs of Handsworth, a draper and shopkeeper. It is apparent that the attractions of the drapery trade were not sufficient for Joseph, for he joined the Varney dyeing business while still a young man. John Varney, who probably ran the business at this time, was Joseph's uncle.

In 1855 he married Miss Harriet Matthews at Carrs Lane Chapel, Birmingham.

In that same year, at the age of 24, Joseph bought his uncle's business for £1,000, and 2 years later he also bought the premises from Varney for a further £400.

The price of £1,000 for the business was not paid at once, but by instalments from the running profits, the final payment being made in January of 1866.

The business was now centred at Oriel House at Bull Street, Birmingham, together with premises in Great Charles Street, which were known as "The Birmingham Central Steam Dyeing & Bleaching Works".

Joseph Harris' business, like Birmingham itself, was booming and growing. By the late 1860s he could be considered a solid businessman, travelling afield in the furtherance of the company, and a large depot was established in Wolverhampton.

By 1867 the company also described themselves as dealers in sewing machines, and quoted many of the leading marques of the time, for which they were agents.

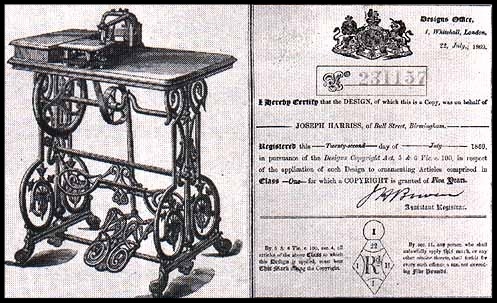

In 1869 Harris was granted a design registration for an ornamental treadle.

Joseph obviously aspired to go further with his sewing machine interests and in 1872, made an agreement with Messrs. Thomas Shakespear and George Illeston, who were trading as The Royal Sewing Machine Company. The arrangement was to supply Harris with a machine to be called "The Challenge", and 40 machines per week would be taken, with a provision for increased production after due notice. Harris was to pay £2.5s.0d for each machine. The agreement also records that The Challenge was to be designed specifically for Joseph Harris, and this to be registered by himself. In consideration of these facts Shakespear and Illeston were prohibited from manufacturing the "Challenge" for any other person, nor were they to undersell Harris with any machine of the same class or type.

It should be noted that the sole exclusivity of design was almost certainly confined to the superstructure, i.e. physical appearance. The mechanics of the machine were, in essence those which were patented by Shakespear and Illeston in 1869, and were used in their own big selling "Shakespear" model. It seems possible that Shakespear and Illeston had similar agreements or collaborations with other customers, viz. Thomas Bradford - Anchor form machines, and J. Collier & Son - Octagonal form machines, to name just two.

During the early 1870s the sewing machine side of the business was proving more profitable than the other departments, with machines being exported as far afield as Australia.

In about 1874 Harris decided the next step forward for his sewing machine enterprise would be to have his own manufacturing facility. To this end, he acquired the Franklin Sewing Machine Company. Franklin and other local firm A. Maxfield already produced a similar class of machine - The "Agenoria". At this same time, Harris, with the aid of John Judson, redesigned and patented a new shuttle / feed mechanism for his "Challenge" marque. Harris was now free of Shakespear and Illeston's middleman roll in his operation, and his sewing machines were then sold under the name of "The Imperial Sewing Machine Co."

For several years the business continued to prosper, and in 1876 Harris applied to register several trademarks for his machines.

As was the case for so many smaller UK sewing machine concerns, the second half of the 1870s brought about fierce overseas competition and a subsequent depression in trade. It would appear that the sewing machine manufacturing side of Harris' empire was unable to weather the storm, and these interests were sold, perhaps somewhat ironically, to The Royal Sewing Machine Co. in about 1877.

The sewing machine department of Harris' did continue to trade for many years, but the high hopes of the early 1870s were never to be fully realized.

The cleaning and dyeing business, in contrast, continued to prosper and the firm was eventually handed down from father to son.

Joseph Harris died at Richmond House, Holyhead Road, Handsworth on 22nd November 1913, aged 82.