- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

Charles Morey

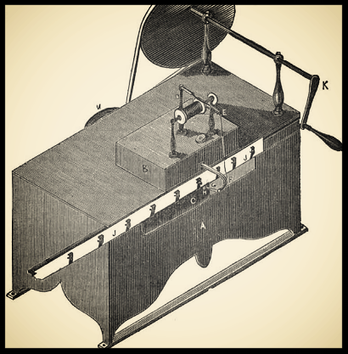

The first sewing machine illustrated and described in any publication in America.

The seventh United States sewing machine Patent US 6.099 was issued to Charles Morey and Joseph B. Johnson on February 6, 1849. Their machine was being offered for sale even before the patent was issued.

In 1848, Mr. Morey was the first person who publicly exhibited a sewing machine in this city and by his enterprise and business tact, he first gave that public impulse to the importance of such machines, which has resulted in their great improvement and wide-spread use at the present day. The event is a painful calamity; he was cut off in the very vigour of health and manhood, suddenly and without a fault on his part, on the very day he was to be liberated from a lingering confinement; perhaps he was in reverie at the prison window, thinking joyfully of his anticipated liberty, when the ball of the stupid and brutal soldier struck him down a lifeless corpse!

An American Inventor Shot in Paris

Recent foreign paper contain an account of the death of Charles Morey of Boston, Mass. He was shot by a sentry while standing at a window of Clichy Debtors’ Prison, in Paris. On the 30th of last month (December 30, 1856). He was proprietor of Goodyear’s patent for vulcanized India rubber for England and France and had been imprisoned through some dispute between him and Mr. Goodyear, ( who has also been residing for some time in France), with the merits of which we are not acquainted. Morey was to have been discharged on the very day he was shot, the court having declared, after a tedious process, that his arrest had been illegal. The sentry stated that he had commanded Mr. Morey to depart from the window, this having been the orders in other prisons and as he did not do so, he fired upon him. A letter in the London Times from an English prisoner says:

“ This morning (30th Dec.) Charles Morey, an American gentleman, patentee of the vulcanized india rubber, was deliberately shot dead by a soldier of the 88th Regt. On guard, when standing with his hands in his pockets at one of the windows which are public to all the inmates. He had committed no infraction of the regulations and these forbid the sentry carrying a loaded musket in the day time. The unfortunate victim, while in prison, was one of its most respected and honoured inmates “.

Mr. Morey was thirty-two years of age and leaves a wife and family. On a few occasions he corresponded with the Scientific American from Europe. He was the joint inventor with Joseph B. Johnson of Boston of a single thread sewing machine.

source: Scientific American

An American company was already manufacturing rubber shoes and boots in France with Charles’ license since the end of 1852. This generated a great deal of prospective business interests. On arriving in France in 1854, Charles Goodyear then placed the reigns of his supervision and management duties with Charles Morey, an enterprising American businessman.

Morey knew French fluently, and would negotiate with the French manufacturers well. Within a few months, his extreme skill and astute business capabilities were for all to see. Charles’ French patent was the first European patent that he received for vulcanized rubber. Under Morey’s leadership, three companies received Charles’ license to start manufacturing vulcanized rubber goods. The first products, mainly rubber shoes, met with tremendous success and the business grew to a healthy magnitude sooner than expected.

As his French business grew rapidly, promising forecasts of huge profits led Charles to plan lavishly for his French exhibition, “Exposition Universelle,” to be held in Paris in 1855. The American committee members, on noticing that very few Americans participated in the exhibition, further insisted that Charles fill up the spaces with his rubber goods. Encouraged, Charles prepared with a nationalistic pledge to represent his motherland and celebrate the aesthetic art of rubber. It cost him fifty thousand dollars for two elegantly designed and centrally placed courts containing beautiful India rubber goods such as rich ornamental jewellery, finely carved caskets, portraits painted on rubber panels, furniture, etc. Since then, trade in the extremely beautiful India rubber jewelry expanded immensely as its popularity increased.

Charles’ exorbitant expenses for this magnificently winning exposition appeared as a sensible investment to him, but Morey’s mismanagement brought him great losses, and it turned out to be ill-fated to his fortunes. Meanwhile, there was an unexpected turn of events as grave complexities loomed in front of the French rubber companies that had begun operations. They lacked the expert manpower to mix rubber compounds and the relevant machinery to work. Simultaneously, Charles’ businesses in America were badly hit as he faced problems in imposing his American patent rights. It caused a ripple effect in the French rubber companies, resulting in a slump in business. Charles’ French patent too was held back for a trifle reason due to which he stopped receiving French royalties. Once again he was bankrupt and in debts.

On 5th December, 1855, Charles was thrown into his familiar ‘hotel’, the debtor’s prison in Paris for 16 days. Mrs. Fanny Goodyear now stood by the side of an extremely fatigued Charles, walking on his crutches. She took on the role of his French interpreter and also requested the help of Charles’ kind business associate to secure his release. In prison, Charles silently bore extreme pain due to gout. It was here that his son conveyed to him that he was conferred with the highest honours from the French Emperor, "Grand Medal of Honor” and the “Cross of the Legion of Honor" for his participation in the French exposition.

source: