- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

AMERICAN PATENT MODELS

1846

Howe Jr.'s Patent Model

US 4.750 September 10, 1846

Elias Howe Jr. of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

While working as a journeyman machinist, Elias Howe Jr. wrestled for years to find a way to mechanize sewing. With the family pinched by poverty, his wife sewed for others by hand at home. Watching her sew, Howe visualized ways to mechanize the process. In 1845, he built his first sewing machine and soon constructed an improved model, which he carried to the Patent Office in Washington to apply for a patent. He received the fifth United States patent (No. 4.750) for a sewing machine in 1846. Howe’s model used a grooved and curved eye-pointed needle carried by a vibrating arm. The needle was provided with thread from a spool. Loops of thread from the needle were locked by a second thread carried by a shuttle, which moved through the loop by means of reciprocating drivers. The cloth hung vertically, impaled on pins on a metal baster plate. The baster plate moved intermittently under the needle by means of a toothed wheel. The length of each stitching operation depended upon the length of the baster plate and only straight seams could be sewn. When the end of the baster plate reached the position of the needle, the sewing was stopped. The cloth was removed from the baster plate and the plate was moved back to its original position. The cloth was repositioned on the pins and the process was repeated until the sewing was finished. This resulted in an imperfect way to sew, but it marked the beginning of successful mechanized sewing. Howe’s patent claims were upheld in court to allow his claim to control the combination of the eye-pointed needle with a shuttle to form a lockstitch. Howe met with limited success in marketing his sewing machine. Subsequent inventors patented their versions of sewing machines, some of which infringed on Howe’s patent. He quickly realized his fortune depended on defending his patent and collecting royalty fees from sewing machine manufacturers. These royalty licenses granted companies the right to use the Howe patent on their machines. In 1856, after years of lawsuits over patent rights, Elias Howe and three companies, Wheeler & Wilson, Grover & Baker and I. M. Singer, formed the first patent pool in American industry. The organization was called the Sewing Machine Combination and/or the Sewing Machine Trust. This freed the companies from expensive and time-consuming litigation and enabled them to concentrate on manufacturing and marketing their machines.

1849

Bachelder's Patent Model

Patent US 6.439, May 8, 1849

John Bachelder of Boston, Massachusetts

John Bachelder submitted this sewing machine patent model for his Patent US 6.439, which was granted on May 8, 1849. Bachelder’s machine sewed with a chain-stitch. He did not claim this chain-stitch mechanism as it was patented earlier in February in 1849 by Charles Morey and Joseph B. Johnson of Massachusetts. Instead he focused on improving the cloth feed. On this model, Bachelder used a wide continuous leather belt inserted with sharp pins to hold the cloth and enable the leather belt to move the cloth forward as it was being sewn. After being stitched, the fabric would be disengaged from the points by a curved piece of metal. This was the first patent for a continuous sewing, intermittent feeding mechanism. Although Bachelder did not manufacture his sewing machine, his patent and later reissues of it were bought by I. M. Singer and became one of the central patents to form the Sewing Machine Combination in 1856. This organization consisted of three sewing machine manufacturers, I. M. Singer Co., Wheeler & Wilson Co. and the Grover & Baker Co. and the inventor, Elias Howe Jr., who all agreed to pool their important patents and stop patent litigation's between them. This allowed them to move ahead with manufacturing and marketing of their own sewing machine and collect license fees from other companies wanting to use their patents.

1851

Grover & Baker's Patent Model

US 7.931 February 11, 1851

William O. Grover and William E. Baker of Roxbury, Massachusetts.

William O. Grover, a tailor working in Boston, believed that the sewing machine would transform the clothing industry. Seeing that the available sewing machines were not very practical, he began in 1849 to devise a different machine. He developed a new stitch that was made by interlocking two threads in a series of slipknots. Another Boston tailor, William E. Baker, shared Grover’s vision and became his partner in the project. They received Patent US 7.931 on February 11, 1851, for a double chain stitch made with two threads. The stitch was made using a vertical eye-pointed needle for the top thread and a horizontal needle for the under thread.The Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company was organized in 1851. Jacob Weatherill, mechanic and Orlando B. Potter, lawyer, joined the firm. It was Potter who saw that the numerous lawsuits over patent rights were strangling the growth of the fledgling sewing machine industry. In 1856, his work lead to the formation of the Sewing Machine Combination also called the Sewing Machine Trust. This organization consisted of three sewing machine manufacturers, I. M. Singer Co., Wheeler & Wilson Co. and the Grover & Baker Co. and the inventor, Elias Howe Jr., who all agreed to pool their important patents and stop patent litigation between them. This allowed them to move ahead with manufacturing and marketing of their own sewing machines and collecting license fees from other companies wanting to use their patents.

1851

Singer's Patent Model

US 8.294, August 12, 1851

Isaac Merritt Singer of New York.

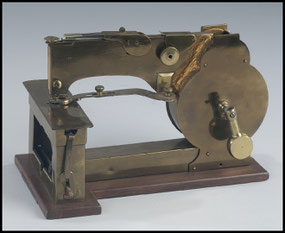

The eighth child of poor German immigrants, Isaac Singer was born on October 27, 1811, in Pittstown, New York. As a young man he worked as a mechanic and cabinetmaker. For a time he was an actor and formed his own theatrical troupe, The Merritt Players. Needing a steadier income, Singer worked for a plant in Fredericksburg, Ohio, that manufactured wooden type for printers. Seeing the need for a better type-carving machine, he invented an improved one. In June 1850, Singer and a partner took the machine to Boston looking for financial support. He rented display space in the workshop of Orson C. Phelps. Here Singer became intrigued with the sewing machine that Phelps was building for John A. Lerow and Sherburne C. Blodgett. Analyzing the flaws of the Lerow and Blodgett sewing machine, Singer devised a machine that used a shuttle that moved in a straight path, as opposed to theirs, which moved around in a complete circle. He visualized replacing their curved horizontal needle with a straight, vertically moving needle. Phelps approved of Singer’s ideas and Isaac worked on perfecting his machine. For his first patent model, Isaac Singer submitted a commercial sewing machine. He was granted Patent US 8.294, on August 12, 1851. These commercial sewing machines were built in Orson C. Phelps’s machine shop in Boston. The head, base cams and gear wheels of the machine were made of cast iron; to fit together, these parts had to be filed and ground by hand. The machine made a lockstitch by using a straight, eye-pointed needle and a reciprocating shuttle. The specific patent claims allowed were for:

1) the additional forward motion of the shuttle to tighten the stitch;

2) the use of a friction pad to control the tension of the thread from the spool;

3) placing the spool of thread on an adjustable arm to permit thread to be used as needed.

Always the showman, Singer relished exhibiting his invention at social gatherings and was masterful in convincing the women present that the sewing machine was a tool they could learn to use. The machine was transported in its packing crate, which served as a stand; it contained a wooden treadle that allowed the seamstress to power the machine with her feet, leaving both hands free to guide the cloth. This early, heavy-duty Singer machine was designed for use in the manufacturing trades rather than in the home.

1852

Miller's Patent Model

US 9.139 July 20, 1852

Charles Miller of St. Louis, Missouri.

At the time of his patent, Charles Miller lived in St. Louis, Missouri, an uncommon choice of residence for a sewing machine inventor. Most of the inventors and subsequent manufacturers, were located in the northeastern United States, particularly New York, Massachusetts and Connecticut. In his patent specification, Miller states: “This invention relates to that description of sewing machine which forms the stitch by the interlacing of two threads, one of which is passed through the cloth in the form of a loop and the other carried by a shuttle through the said loop”. His claim continues by stating: “It consists, first, in an improved stop-motion, or certain means of preventing the feed or movement of the cloth when by accident the thread breaks or catches in the seam and, second, in certain means of sewing or making a stitch similar to what is termed in hand-sewing "the back stitch". According to Miller, his mechanism was different in that it passed the needle through the cloth in two places rather than in one, as was the case with other sewing machines of the time. His brass model is strikingly handsome and engraved on the base of the model is “Charles Miller & J. A. Ross”. Usually when a second name is so prominently displayed on a model, it indicates a second inventor. However, no mention is made of Ross in the patent specification. Interestingly, Jonathan A. Ross turns up the following year at the 1853 New York Exhibition, exhibiting a sewing machine and is listed in the catalogue as a sewing machine manufacturer from St. Louis, Missouri. Miller is perhaps best known for an invention some two years later. It was the first sewing machine patented to stitch buttonholes (Patent US 10.609, issued March 7, 1854). In his patent specification, Miller describes the three different stitches, button-hole stitch, whip stitch or herring-bone stitch, that can be mechanically sewn to finish the buttonhole.

1852

Bradeen's Patent Model

US 9.380 November 2, 1852

John G. Bradeen of Boston, Massachusetts.

John G. Bradeen notes in his patent specification that his sewing machine operates and forms a similar stitch to that of Frederick R. Roberson’s sewing machine of December 10, 1850 (Patent US 7.824.) Roberson’s machine sewed with a running stitch or basting stitch. The mechanisms of Bradeen’s patent model are mostly made of brass and the model sits on a simple wooden box. He furnished six pages of drawings depicting his improvements, whereas most sewing machine inventors limited their submissions to fewer drawings. Bradeen claims for his improvements “two rotating draft-hooks . . . separate from the needle, in combination with the two needles and two threads-guides; . . . the arrangement of each needle and its thread-guide, respectively, on opposite sides of the cloth . . . and the combination of the rocking thread-lifter or its equivalent with the needle and presser . . . .” It is not known if any sewing machines were manufactured based on Bradeen’s patent.

1854

Hunt's Patent Model

US 11.161, June 27, 1854

Walter Hunt of New York.

Walter Hunt was born in rural Martinsburg, New York, on July 29, 1796. The nearby town of Lowville was the site of a textile mill where Hunt’s family worked. Hunt, adept at providing mechanical solutions to difficult problems, worked with the mill owner, Willis Hoskins, inventing and patenting improvements to the flax spinner in 1826. He traveled to New York City to raise capital for manufacturing the device. Hunt supported his family in New York by speculating in real estate, but his love of creativity was paramount. From 1829 to 1853 his inventions and patents included a knife sharpener; a rope making machine; a heating stove; a wood saw; a flexible spring; several machines for making nails; inkwells; a fountain pen; a bottle stopper; firearms and a safety pin. In 1833, Hunt invented a sewing machine that used a lockstitch, but failed to patent it. The lockstitch used two threads, one passing through a loop in the other and then both interlocking. This was the first time an inventor had not mimicked a hand stitch. As Joseph N. Kane writes in Necessity’s Child: The Story of Walter Hunt, America’s Forgotten Inventor, “With nothing to serve as a basis or model, with no other machine from which parts could be obtained, he evolved a plan for mechanical sewing which was so revolutionary that had he even dared to suggest it before completion of his model he would have been scoffed at and regarded as insane.”Ten years later, manufacturers searched for ways to mechanize sewing and inventors turned their energies to patenting improvements to sewing machines. On May 27, 1846, Elias Howe Jr. received Patent US 4.750 for improvements to the sewing machine, claiming to have created the first machine to sew a lockstitch using two threads. When Howe began to sue manufacturers for royalties, Hunt’s previous work emerged as attorneys argued that Hunt’s invention preceded Howe’s and therefore Howe’s patent claims were invalid. On April 2, 1853, Hunt submitted his application for his 1834 sewing machine, as his invention preceded Howe’s machine. The Patent Office recognized Hunt’s precedence but it did not grant a patent to Hunt because he had not applied for one prior to Howe’s application. Hunt received public credit for his invention, but Howe’s patent remained valid because of a technicality. Later, Hunt was granted a patent for other improvements on the sewing machine. In Hunt’s patent specification for Patent US 11.161, issued on June 27, 1854, he claimed: “Said improvements consist in the manner of feeding in of the cloth and regulating the length of the stitch solely by the vibrating motion of the needle; in a rotary table or platform, upon which the cloth is placed for sewing; in guides and gages for controlling the line of the seam. ”Hunt noted that other sewing machines would jam because the material had to be pushed through the vibrating needle. He created a round rotating top that allowed the cloth to be fed through the needle at an even rate, eliminating the problem of jamming. As in the past, Hunt simply sold off the rights to the machine to others and did not capitalize on it, but he did prove that he had the mechanical ability and the creativity to improve upon the sewing machine.

Hunt continued to invent and patent devices until his death in 1859. Several were patented: shirt collars, a reversible metallic heel for shoes, lamp improvements and a new method for manufacturing shirt fronts, collars and cuffs. Walter Hunt’s inventive nature was captured in the New York Tribune, which wrote at his death,

“For more than forty years, he has been known as an experimenter in the arts. Whether in mechanical movements, chemistry, electricity or metallic compositions, he was always at home and, probably in all, he has tried more experiments than any other inventor”.