- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

Room 12

GENIUS REWARDED

or,

THE

Story of the Sewing Machine

1880

by John Scott

CHAPTER I

THE SEWING MACHINE'S RIVALS

" With fingers weary and worn, With eyelids heavy and red, A woman sat, in unwomanly rags, Plying her needle and thread, Stitch ! stitch ! stitch! In poverty, hunger and dirt, And still, with a voice of dolorous pitch, Would that its tone could reach the Rich ! She sang the ' Song of the Shirt."

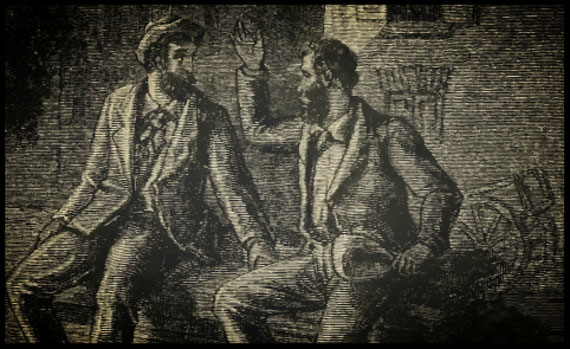

In a back street of Boston two men sat one sultry August midnight upon a pile of boards. They were penniless and friendless; they were smarting under failure and keen and bitter disappointment. Actual want stared them in the face and made them desperate.

3

And yet, upon the outcome of that midnight scene mighty issues hung quivering. All the world had a stake in the thoughts of those poor, friendless, desperate men. One of them had heard from across the seas the " Song of the Shirt;" he had heard its sad echo even from the more prosperous homes of our own land, and its dismal chords had awakened in his breast a burning desire to still its horrible refrain, and carry relief and help to the weary seamstress. Golden visions, too, had floated before him of the princely reward the world would offer for such service to its great sisterhood. With great difficulty he had persuaded two other men to join him. One furnished the scanty capital of forty dollars; the other gave the use of his machine shop, workmen and tools. Day and night he had worked to produce a SEWING MACHINE, sleeping but three or four hours out of the twenty-four, and eating, generally, but once a day, as he knew the machine must be built for forty dollars or not be built at all. The hour of trial had come that very day. The machine had been completed and put together, and did not work ! One by one the workmen left him in disgust, but still the inventor clung tenaciously to his purpose, and refused to yield to defeat. All were gone but this companion, who held the lamp while the inventor worked. Loss of sleep, insufficient food, and incessant work and anxiety made him weak and nervous, and he could not get tight stitches. Sick at heart, the task was abandoned at last, and at midnight the worn and wearied men turned their backs upon their golden dreams and started for their lodgings. On their way they sat down upon the pile of boards, and were gloomily discussing the sad fate of the project, when his companion mentioned to the inventor that " the loose loops of thread were all upon the upper side of the cloth." Instantly it flashed upon the inventor what the trouble was, and back through the night the men trudged to the shop, re-lighted the lamp, tightened a little tension screw, and in a few minutes Isaac Merritt Singer had produced the first Sewing Machine that ever was practically successful.

4

5

It was a great stake which the world had in the gloomy midnight reflections of two desperately poor men, seated upon that pile of boards, thirty years ago ! Rarely has so much hung upon the thoughts of two humble men. That midnight scene settled the question whether woman should have a tireless helper in her weary task of stitching whether or not the world should thenceforward have a machine for sewing. Out of that lumber-pile conference came the Sewing Machine and all the mighty interests involved in its manufacture, sale, and use. It was the answer to the " Song of the Shirt;" its dolorous tone had reached—not the rich—but a poor, struggling mechanic; and his invention has done for woman and for the home circle what no other invention ever has done. We look back upon James Watt, sitting before the open fireplace, watching the pot lid rise and fall with the then undiscovered power of steam, as the scene whence issued all the blessings which followed the Steam-engine. We think of Franklin flying his storm-riding kite and drawing down the lightning, as thereby bringing to us all the civilizing influences of the Telegraph. But neither of these men, if they could have looked down the dim vista of the coming centuries, and foreseen what their inventions should do for humanity, could have contemplated results more surprising than those which Isaac Merritt Singer lived to see crowning the invention which hung trembling upon the results of that talk upon that pile of boards! The Telegraph and Steam-engine live daily in the broad blaze of public view; the Sewing Machine modestly hides itself away beneath three million of the nine million roofs of America. They are public blessings; the Sewing Machine is a purely domestic one. It earns a woman's dime; they earn a railroad king's millions. They deal with the great arteries of trade and commerce; it deals with the fireside circle.

6

The Telegraph and Steam-engine proudly boast their alliance and familiarity with Capital; the Sewing Machine contentedly takes up its humble quarters mainly with people who never drew a dividend in all their lives. Capital and wealth must run the former; slender and humble feet most often run the latter. The Locomotive puffs defiantly in nearly every legislative hall; the Sewing Machine sings its tireless tune to ears that would not know what "lobby" meant. The former haughtily issues its dictum to primaries and conventions; the latter could not control a solitary vote. Steam and the Telegraph deal mainly with creation's lord; the Sewing Machine with his lowlier sister. A certain class of people are apt to underrate domestic affairs, simply because they are domestic, forgetting that the real progress of the world is always made beneath the shelter of the homestead roof, not under the resounding domes of Senate Chambers; and that a Nation's surest hope for greatness and for safety is found in the character of its homes, rather than in the shrewdness of its merchants or the skill of its artisans. It is the atmosphere of the boy's early home which clings like an indestructible and exhaustless aroma to his entire life; it is the influence and memory of what his home and his mother were which mould his after life, control his habits of thought, and make him a power for good or for evil in the world. And for the most part he remains unconscious of any such influence. He has imbibed it with his daily sustenance and inhaled it with every breath of his native air, until he involuntarily weighs everything, measures all affairs, and judges all men according to the standards and traditions that prevailed in the now hallowed precincts of his early home. Whatever, therefore, brings added comfort to the matron and the maiden; whatever saves the busy housewife's time and increases her opportunities for culture; whatever lifts any of the heavy household burdens, and disenthralls to any degree the women of our day, contributes an ever augmenting influence towards the highest and best progress of the world.

7

And so the importance of the Sewing Machine in its influence upon the home; in the countless hours it has added to woman's leisure for rest and refinement; in the increase of time and opportunity for that early training of children, for lack of which so many pitiful wrecks arc strewed along the shores of life; in the numberless avenues it has opened for female labor; and in the comforts it has brought within the reach of all, which once could be attained only by the wealthy few, becomes so apparent that few, if any, will dispute its right to stand at least beside its powerful rivals, the Steam-engine and Telegraph.

8

CHAPTER II

GROWTH OF THE IDEA

The idea of sewing by machinery had been cherished for a hundred years before the first successful machine was built. The earliest attempt at sewing by machinery of which any authentic account exists was made as early as July 24th, 1755, when a machine was patented in England by Charles F. Weisenthal, having a needle with two points and an eye at mid-length. The next sewing machine was that of Thomas Saint, of England, who obtained a patent July 17, 1790. This man seems to have understood, with remarkable clearness, the main essential features of the invention, for his machine had a horizontal cloth-plate, an overhanging arm, at the end of which was a needle working vertically, and a " feed " working automatically between the stitches. These features have been preserved in every successful machine ever made. The needle was notched at the lower end, to push the thread through the goods, which had been previously punctured by an awl. As the needle passed up-wards, leaving a loop in the thread, a loop-check caught the loop and held it until the needle descended again, enchaining the thread of the new loop in the former one. In 1804 an Englishman, named Duncan, made a chainstitch machine, having a number of hooked needles, which passed through the cloth and were supplied with thread beneath the goods by a feeding needle, whereupon the needles receded, each drawing a loop through the loop previously drawn by itself through the cloth. In 1818 Rev. John A. Dodge, of Monkton, Vt., invented, and, with the assistance of John Knowles, an ingenious mechanic, constructed a machine having the double-pointed needle and eye at mid-length.

9

It made a stitch identical with the ordinary " back-stitch," and was furnished with an automatic device for " feeding " the work. Mr. Dodge never applied for a patent, nor attempted to manufacture any more machines, because of the great pressure upon his time as a pastor, and further on account of the bitter opposition of journeymen tailors, who denounced the machine as an invasion of their rights. The first patent issued in America for a sewing machine was that of a man named Lye, in the year 1826.Lye's device could hardly have contained any useful or striking features, for when the fire of 1836 destroyed all the Patent Office Records, it consumed all that remained of this machine. In the year 1830 Barthlemy Thimmonnier, a Parisian, invented a machine which operated much as Saint's did, except that the needle was crochctted, and, descending through the goods, pulled up a lower thread and formed a series of loops vipon the upper side of the goods. Eighty of these machines, made of wood, are said to have been used at one time in Paris, making army clothing ; but though patented in France in August, 1848, and in the United States September 3, 1850, it had too many defects to become anything more than an important step in the onward march of this great invention. Many other machines, of more or less merit, were constructed before Mr. Singer made his machine, but all fell short of being practical and useful. The nearest approach to success prior to 1850 was made by Walter Hunt, of New York City, in the years 1832-3-4. His machine had a curved needle, with an eye near the needle-point, which was operated on the end of a vibrating arm. A loop was formed beneath the cloth by the needle-thread, through which a shuttle, reeling off another thread, was forced back and forth with each stitch, making an interlocked stitch like that now made by the best machines.

10

11

George A. Arrowsmith, a blacksmith, of Woodbridge, N. J., being of a speculative turn, bought one-half of Walter Hunt's invention in 1834, and afterwards acquired the remainder. Soon afterwards, Adoniram F. Hunt, a brother of Walter, was employed by Arrowsmith to construct some sewing machines upon the same principle, but differing somewhat in arrangement of details from the original. These machines were made and operated at a machine shop in Amos Street, New York City. Arrowsmith neglected to obtain a patent upon the machine for reasons which, in the light of events now past, make singularly interesting reading. He assigned three reasons for not procuring a patent : (1) He had other business ; (2) the expense of patenting ; (3) the supposed difficulty of introducing them into use, saying, it " would have cost two or three thousand dollars to start the business." There appeared also a prejudice against any machine which had a tendency to dispense with female labor. A proposition made by Walter Hunt to his daughter to engage in the corset-making business with a sewing machine was declined, after consultation with her female friends, principally, if not altogether, as she afterwards testified, "on the ground that the introduction of such a machine into use would be injurious to the interests of hand-sewers. I found that the machine would at that time be very unpopular, and, therefore, refused to use it." The neglect of Hunt and Arrowsmith to procure a patent upon this sewing machine Avas fraught with momentous consequences a few years later, not only to them but to the entire sewing machine trade and the world at large. John J. Greenough, on February 21, 1842, procured the first sewing machine patent in America of which any official record now exists.

12

His machine sewed with two threads, both of which were entirely passed through the cloth at every stitch, the needles being pulled by pincers through holes previously bored with an awl. It was designed principally for leather work. R. W. Bean, of New York City, patented a machine, March 4, 1843, for making a "running" or basting stitch. Another machine, having two threads and generally like Greenough's, was patented December 27, 1843, by George R. Corliss, of Greenwich, N. Y. It had eye-pointed needles reciprocated in horizontal paths, through holes previously made by awls, the goods being fastened between clamps and fed in front of the needles. Another form of sewing machine, of which several varieties were patented between 1844 and 1850, adopted the somewhat primitive method of first crimping the cloth and then forcing it upon the needle, which was driven through a number of thicknesses at the same time, making a running stitch. In the year 1846, or over twelve years after Walter Hunt's machine was built, Elias Howe, Jr., having probably ascertained that Hunt had never patented his machine, built a sewing machine upon the Hunt plan, adding two puerile devices (both of which were subsequently abandoned as useless), and procured a patent thereon in his own name.

13

These devices were a " clipping piece " to control the unwinding of the shuttle-thread, and a " baster-plate," to which the work was basted, and thus hung vertically in front of the machine. This machine never became of real utility until the inventions of Mr. Singer, five years later, had been added to the principles of action applied originally by Hunt and appropriated by Howe. After Singer's inventions had been recognized as giving to the sewing machine a practical and immense value, Walter Hunt testified, under oath, as follows : " Elias Howe has several times stated to me that he was satisfied that I was the first inventor of the machine for sewing a seam by means of the eye-pointed needle, the shuttle and two threads, but said that he had the prior right to the invention because of my delay in applying for letters-patent." In the year 1853, Hunt applied for a patent upon his invention, but was refused upon the ground of abandonment. Judge Charles Mason, Commissioner of Patents, in delivering his decision in May, 1854, upon the evidence in Hunt's application, used the following language: " Hunt claims priority upon the ground that he invented the Sewing Machine previous to the invention of Howe. He proves that in 1834 or 1835 he contrived a machine by which he actually effected his purpose of sewing cloth with considerable success. Upon a careful consideration of the testimony, I am disposed to think that he had then carried his invention to the point of patentability. I understand from the evidence that Hunt actually made a working machine in 1834 or 1835. The papers in this case show that Howe obtained a patent for substantially this same invention in 1846." Notwithstanding this, the Commissioner was forced to refuse Hunt's belated application, for the reason that an Act of Congress in 1839 had provided that inventors could not pursue their claims to priority in patents unless application was made within two years from the date when the first sale of the invention was made.

14

15 (the picture of this page was relocated)

Hunt had sold a machine in 1834, and had neglected to make application for his patent till 1853. Thus it was that one of the grandest opportunities of the century was missed by the man who should rightfully have enjoyed it ; the honors and emoluments of the great sewing machine invention passed to a man who neither had invented a single principle of action, nor applied a practical improvement to principles already recognized ; and Elias Howe, Jr., acquired the power, by simply patenting another man's invention, to obstruct every subsequent inventor, and finally to dictate the terms which gave rise to the great Sewing Machine Combination about which the world has heard — and scolded — so much. Howe's machine was not, even in 1851, of practical utility. From 1846 to 1851 he had the field to himself, but the invention lay dormant in his hands. He held control of the cardinal principles upon which the coming machine must needs be built, and planted himself squarely across the path of improvement — an obstructionist, not an inventor — and when, in 1851, Isaac M. Singer perfected the improvements necessary to make Hunt's principles of real utility, Howe, after long and expensive litigation, laid Singer and all subsequent improvers under heavy contribution for using the principles of Hunt, patented by himself. Morev & Johnson procured a patent February 6, 1849, for a single-thread machine, making a stitch by a hook acting in combination with a needle. Lerow & Blodgett patented a machine October 2, 1849, the peculiar feature of which was that the shuttle was driven entirely around a circle at each stitch. This took a twist out of the thread at every revolution, and was soon abandoned, but not before Howe had sued the proprietors and laid them under tribute.

16

Allen B. Wilson invented a double-pointed shuttle, making a stitch at each passage of the shuttle, which he patented November 12, 1850. Grover & Baker, February 11, 185 1, obtained a patent for a machine using two needles, one passing through the goods and the other operating beneath the cloth. Other patents, of more or less value, were obtained, but not yet had a sewing machine of any practical working value been produced.

17

Machines had been made by hundreds, factories liad been built for their manufacture, territorial rights had been sold for machines that contained more or less merit, but which would not and could not do continuous stitching. The idea of a successful substitute for woman's deft fingers at sewing had come to be regarded much as the member of Parliament viewed the project of an ocean steamship, when he offered to " eat the first ship that should cross the Atlantic by steam !" The sewing machine had bitterly disappointed those who purchased it for use in the household ; it had bankrupted those who sought to manufacture; it had turned to ashes upon the lips of those who bought territorial rights. If any one had profited by it, it was the vendor of territorial rights. Indeed, a sewing machine patentee named Blodgett told Singer he was an idiot for presuming to make sewing machines to sell. They would not work, and the only money to be made out of the business was in " selling territorial rights." Deep-seated distrust pervaded the public mind, and well-deserved odium had settled upon the entire invention. Such was the state of affairs when Isaac M. Singer turned his versatile mind towards the Sewing Machine.

18

CHAPTER III

THE FIRST SINGER MACHINE

The humble origin of the first practically successful sewing machine was told by Mr. Singer himself a few years before his death. We reproduce the interesting narrative in his own language:" My attention was first directed to sewing machines late in August, 1850. I then saw in Boston some Blodgett sewing machines, which Mr. Orson C. Phelps was employed to keep in running order. I had then patented a carving machine, and Phelps, I think, suggested that if I could make the sewing machine practical I should make money." Considering the matter over night, I became satisfied I could make, them practically applicable to all kinds of work, and the next day showed Phelps and George B. Zeiber a rough sketch of the machine I proposed to build. It contained a table to support the cloth horizontally, instead of a feed-bar from which it was suspended vertically in the Blodgett machine, a vertical presser-foot to hold the cloth, and an arm to hold the presser-foot and needle-bar over the table." I explained to them how the work was to be fed over the table and under the presser-foot, by a wheel having short pins on its periphery, projecting through a slot in the table, so that the work would be automatically caught, fed, and freed from the pins, in place of attaching and detaching the work to and from the baster-plate by hand, as was necessary in the Blodgett machine." Phelps and Zieber were satisfied that it would work. I had no money. Zieber offered forty dollars to build a model machine. Phelps offered his best endeavors to carry out my plan and make the model in his shop. If successful we were to share equally. I worked at it day and night, sleeping but three or four hours out of the twenty-four, and eating generally but once a day, as I knew I must make it for the forty dollars, or not get it at all. The machine was completed in eleven days. About nine o'clock in the evening we got the parts together, and tried it. It did not sew.

19

The workmen, exhausted with almost unremitting work, pronounced it a failure, and left me one by one. Zieber held the lamp, and I continued to try the machine; but anxiety and incessant work had made me nervous, and I could not get tight stitches. Sick at heart, about midnight we started for our hotel. On the way we sat down on a pile of boards, and Zieber mentioned that the loose loops of thread were on the upper side of the cloth. It flashed upon me that we had forgotten to adjust the tension on the needle-thread.

20

We went back, adjusted the tension, tried the machine, sewed five stitches perfectly, and the thread snapped. But that was enough. Persistent efforts have been made by interested parties to create an impression upon the public mind that it was Mr. Howe who first evolved order out of the chaotic essentials of the sewing machine and brought it into practical use. Of this let the reader judge for himself, after comparing the features of each machine set forth below. Let him note the features that are still preserved in every successful sewing machine and those which have been abandoned as practically worthless, and he will find little difficulty in settling for himself the merits of the respective claims of Howe and Singer.

HOWE'S MACHINE

HAD SINGER'S

MACHINE HAD

curved needle 1 straight needle

(Now obsolete in

machines of this class) (Now in general use)

***

needle arm swinging like a 2 needle bar moving vertically

pendulum in an arc of a circle

(Now obsolete)

(Now in general use)

***

A clamp, or baster plate from 3 A horizontal table, upon which

which the work was hung the work was laid flat, by

vertically in front of the machine. means of which it could be

In order to make a turn in the instantly and readily turned

seam, the machine had to be in any direction

stopped, the goods taken off

from the plate, and then

readjusted to it.

(Now obsolete) (Now in general use)

***

A feed motion imparted to the 4 A feed motion imparted by means

basterplate by the teeth of an of a roughened feed wheel

intermittently moving pinion, extending through a slot in the

working into the holes of the top of the table

baster-plate, from which the

work was suspended, which

had to be readjusted every

time a seam had been sewed (Replaced by the present

the length of the plate feed, similar in principle

(now obsolete) but improved in action)

***

Two shuttle-drivers, entirely 5 Two shuttle carriers attached

distinct from each other, which to the same bar, sliding

threw the shuttle from side to steadily and regularly in a

side, producing violent horizontal groove

concussions, and liable to throw

the shuttle drivers out of place

(now obsolete) (now in general use)

***

************* 6 A spring presser-foot by the side of

************* the needle, to hold the work down

(now in general use)

***

************* 7 An adjustable arm for holding

************* the bobbin containing the

needle-thread

(now obsolete)

***

A single acting treadle 8 A double acting treadle

(now obsolete) (New in universal use)

***

An eye-pointed needle 9 An eye pointed needle

(Invented by Walter Hunt) (Invented by Walter Hunt)

********************* 21 and 22 ***********************

The tests of time and actual service have been applied to the original features of both machines, and these, at least, know no favoritism. It matters not in these tests how broad or loud is the claim of any man; history may be blinded for a time, but the "survival of the fittest" is the inexorable law in useful inventions. None of the devices used by the man who claims to have " invented the sewing machine " can be found in any successful shuttle machine to-day. Thirty years of actual service have swept away every vestige of Howe's original machine except the eye-pointed needle, invented twelve years before by Walter Hunt, and used by both Singer and Howe. Meanwhile every feature of Singer's original machine has been adopted by every successful machine builder of the class to which these machines belonged, with the single and unimportant exception of the adjustable arm; and in nearly every case when a device of Howe's has been found worthless, and been abandoned, it was Singer's device which was substituted, as the foregoing table explicitly shows. In the clear light of such facts it is not difficult to understand to whom the world is really indebted for the inestimable boon of the sewing machine.

23

CHAPTER IV

GREAT OAKS FROM LITTLE ACORNS

Starting with a capital of forty dollars, and that borrowed from another man, this poor mechanic launched upon the stormy sea of commercial life. Discouragements and disappointments met him at every turn. People had learned to look upon the Sewing Machine very much as we look upon the " Keely Motor." Every man who pretended to have a working machine was considered an impostor. Thousands had bought machines on the faith of inventors' statements, which they were obliged to throw aside as useless. Whoever now attempted to introduce the Sewing Machine must face all the consequences of previous failures, and this Mr. Singer quickly learned to his sorrow. Everywhere he found people unwilling to believe that a successful sewing machine had actually been built, and repeatedly he was shown to the door the moment he had stated his business. Mr. Blodgett advised him to give up manufacturing, and sell territorial rights. He said he was a tailor by trade and knew more about sewing than Singer possibly could ; that the Blodgett machine had been the leading machine in the market, and he could rest assured that " sewing machines would never come into use." Still the undaunted mechanic struggled on in poverty, bearing up under reverses and disappointments, resolved to force an unwilling public to recognize the fact that a successful sewing machine could and actually had been made. Slowly he gained ground ; gradually he obtained access to the public ear ; by degrees he induced people to at least give his machines a test. A few hundred dollars borrowed from friends expedited the work of introduction, and just as the skies seemed to brighten, a new and formidable trouble appeared. The news that Singer had made a machine which would actually do continuous stitching brought Elias Howe, Jr., to his door with the patent he had obtained upon another man's invention (as before stated), who claimed that Singer infringed his patent, and must pay him the modest sum of $ 25.000 or quit the business. It did not take long for a man who had recently borrowed forty dollars to begin business, to decline paying twenty-five thousand dollars tribute-money, and the consequence was that Singer found himself burdened with litigation that threatened to swamp him.

24

25

At this juncture he called in the aid of Mr. Edward Clark, whose recognized legal and financial skill were taxed to the utmost to prevent the utter ruin of the inventor. Mr. Clark became an equal partner, and business was thenceforward conducted under the firm name of "I. M. Singer & Co." Other inventors were stimulated by Singer's success to vigorous efforts at making machines of practical utility, and the consequence was a series of infringements upon existing patents, resulting in a perfect epidemic of litigation. Principal among the litigants was Elias Howe, Jr., whose patent enabled him to bring all the rest under contribution, and this he did, sueing right and left for several years. The patent of 1846 had made Howe complete master of the situation, and enabled him to dictate the formation of a combination, by the terms of which licenses were issued to manufacturers upon the payment of a heavy royalty for each machine manufactured. From this royalty Howe received the monstrous stipend of over two millions of dollars, not because he had invented anything useful to the world, but simply because he had obtained a patent upon the inventions of another man ! From the outset, Singer & Co. resisted, at great expense, the demands and pretensions of Howe, fighting single-handed the battle of the inventors and the great world which was waiting for cheap machines. Howe was endeavoring to establish a monopoly, strong and compact, which meant dear machines to the weary-fingered women who were still singing the dreary " Song of the Shirt;" Singer & Co. were struggling to throw the business open to fair and honest competition at moderate prices. For three years the unequal contest was continued against the monopoly. All the other manufacturers had yielded to Howe at the first, and were conducting their business without interruption under his licenses.

26

27

They viewed the contest between Howe and Singer & Co. much as the traditional frontiersman's wife regarded a terrible struggle between her husband and a grizzly, merely remarking that " it didn't make much odds to her which won, but she allers loved to see a right lively fight." If Singer & Co. won, all the others would reap the full benefit of the victory without cost to themselves ; if Howe should win, they would be no worse off than they were before, and he would probably cripple their most formidable competitor. Meanwhile the business of Singer & Co. was suffering every possible obstruction, while that of their competitors, now wholly uninterrupted, was making great strides. At last, in May, 1854, self-preservation dictated a withdrawal from such a contest, and an agreement was made by which Singer & Co. were to pay Howe a royalty upon each machine manufactured by them. Thus was taken the last and most important step towards the great Sewing Machine Combination, into which Singer & Co, were the last to enter, and then only when driven into it for self-preservation, after a long and exhaustive drain upon their means. In settlement of this suit, Howe received $15,000 royalty, and the total sum paid to Howe by Mr. Singer and his associates, up to 1877, was over a quarter of a million dollars. By the year 1863, the annual sales of Singer machines amounted to 21,000, and agencies were established in the principal cities of the United States. In that year the firm was merged into an incorporated company, bearing the title of " The Singer Manufacturing Company," and both the original partners retired from the active management of the business, though they remained the heaviest stock-holders, and had seats in the Board of Directors. In four years' time the yearly sale of machines had more than doubled. In two years more even this large figure had been doubled. Two years more and the annual sales had again doubled, the sales of that year (1871), amounting to 181,260 machines.

28

In seven years more even this amount of business was doubled, the number of Singer machines sold in the year 1878 being 356,432. It would seem as if the extreme limit of business must now have been reached. But still the yearly sale increased, and, in the single year, 1879, the world bought the immense number of 431,167 Singer Sewing Machines, and, at the time of writing, it appears as though even this figure might be surpassed for the year 1880. Three-fourths of all the sewing machines sold throughout the world in 1879 were " Singers." Perhaps no company ever before was officered as the Singer Manufacturing Company was at its organization in 1863. The business had been originally started by a penniless man upon a borrowed capital of forty dollars, and had brought to him and his partner a golden harvest. Both were now rich, and in stepping out they placed the control of the new Company in the hands of men who had risen to notice solely by their own merits and exertions.The new President, Mr. Inslee A. Hopper, had been an entry clerk with I. M. Singer & Co.; the Vice-President and General Manager was found in the person of Mr. George R. McKenzie, who had been a joiner and cabinet maker for the old firm at eleven and a half dollars a week. He was a hard-working mechanic, whose solid business worth and prodigious ability as an organizer and an executive took him by degrees to the post of General Manager of a business giving employment to forty thousand men, which post he fills to-day with eminent and acknowledged skill. The Secretary was Dr. Alexander F. Sterling, a physician of New York City, who possessed an unusual tact for business; and the Treasurer's post was assigned to Mr. William F. Proctor, who had spent years at a machinist's bench, and whose practical judgment and skill in mechanics are important elements to this day in the management of the business.

29

In 1876 Mr. Hopper resigned, and Mr. Edward Clark was unanimously called to the Presidency of the Company, and the active management of the business to whose early days he had devoted his abilities with such signal success. Nor are these the only instances where men have risen from the ranks to high position in the Singer Company. Many years ago, when the old firm was battling with poverty, Mr. Singer sent a bright, energetic , but poor young man, to New Haven, Conn., to open an office and try to establish a business in Singer machines, saying to him, ''Jim, we will send you all the machines you want, but not a cent of money." It was the practical application of the polite Southern phrase, " Root, hog, or die." The young man fought his way to business with desperate energy, and to-day is manager of the Central Office at Chicago, having a district covering several States and Territories, and has, within a single year, sold over two million dollars worth of Singer Sewing Machines. Another young man, who worked as a clerk at six dollars a week in this same New Haven office, is now manager of the immense office at London, which manages the Company's business in Great Britain and Ireland, France, Spain, and Western Europe generally, also Africa, Australia, South America and the British Possessions of Asia. Not many years since, a bright German boy was employed in the factory, carrying water for the men and doing odd jobs. He did his trivial duties well, however; so well that he was rapidly pushed forward. Step by step he was promoted, and now is manager of the great Singer office at Hamburg, Germany, which does a vast business throughout Central and Eastern Europe, and is pushing its way into Western Asia. Like the others, he began without friends or influence, and has won his present proud position by faithful adhesion to duty in the humblest post, by modest energy and strict integrity.

30

31 (the picture of this page was relocated)

The Central Office managers at Cincinnati and St. Louis, each doing a large business and entrusted with great interests and responsibilities, began at the lowest round of the ladder, and have climbed unaided to their present positions. Surely there has been no royal road to position in this remarkable company. It is doubtful if the history of the entire world can furnish an instance in which any single house, doing a legitimate business, has had a growth so stupendous within an equal length of time. The reader will remember that Arrowsmith, the purchaser of Hunt's first machine, failed to patent the invention because, among other reasons, it would require "at least three thousand dollars " to begin the business of manufacturing and selling sewing machines. Little did he dream that within thirty years a single company would have millions of dollars invested in the manufacture of one form of sewing machine ! Arrowsmith urged for his fatal delay in procuring the patent to which he was then entitled, that the fees were so heavy — some $ 60! And now one company spends thousands of dollars annually in the various forms of advertising ! Still another reason urged by this enterprising smithy was that he " had other business." Yet, within thirty years a single company finds itself with over ten thousand employes under regular salaries or wages, and thirty thousand more working the whole or part of the time on commission. And this Company, investing many millions of money in its business, spending thousands every year in advertising, employing some forty thousand persons, eight thousand horses, and having its own locomotive and steamboat busy in transporting its machines and materials between New York and its great factory at Elizabeth, is, as the reader may have surmised.

32

33 (the picture of this page was relocated)

The Singer Manufacturing Company. Its system of agencies embraces the entire civilized world, and even pushes its outposts across the boundaries into semi-civilized lands. All of the United States and Canada are covered with this grand network of agencies; Mexico, the West Indies, and South America are familiar with the name "Singer." Every nook and corner of Europe knows the song of this tireless Singer, too, and so do the colonized portions of Africa, Asia, and Australasia. An immense business is done in Singer machines in Australia ; thriving agencies and sub-agencies may be found throughout China, Japan, and the Islands of the Indian Ocean. Calcutta has a large business in Singer machines, and even Cape Town and Transvaal, in South Africa, are giving the Singer agents an increasingly large patronage. On every sea are floating the Singer Machines ; along every road pressed by the foot of civilized man this tireless ally of the world's great sisterhood is going upon its errand of helpfulness. Its cheering tune is understood no less by the sturdy German matron than by the slender Japanese maiden ; it sings as intelligibly to the flaxen-haired Russian peasant-girl as to the dark-eyed Mexican Senorita. It needs no interpreter, whether it sings amid the snows of Canada or upon the pampas of Paraguay; the Hindoo mother and the Chicago maiden are to-night making the self-same stitch ; the untiring feet of Ireland's fair-skinned Nora are driving the same treadle with the tiny understandings of China's tawny daughter ; and thus American machines, American brains, and American money are bringing the women of the whole world into one universal kinship and sisterhood. The Principal Office of the Company is finely located in New York City, overlooking Union Square. From this office the general business of the Company is directed all over the world.

34

35

The American business is transacted from twenty-five centres, located in the larger cities, such as Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Richmond, Cincinnati, St. Louis, etc. Each Central Office is controlled by a manager, under whose direction Branch Offices are located throughout the territory assigned to his care. Under the Branch Office agent, again, are located subordinate offices in every town or village within his district where business seems to warrant it. The territory controlled by a Central Office often embraces an entire State, and, in some cases, several States. In other instances two or more Central Offices are located within the same State. While the Central Office manager is charged with the general direction of all his Branches, and the Branch Office agent with the care and management of all his subordinate offices, yet the reader should not suppose these superior offices to be nothing but a sort of head-quarters for the officers of higher rank. Every Central Office is equipped with its force of canvassers, collectors, etc., and is expected to accomplish as much of the actual work of canvassing and selling as though it were the only office the Company ever opened. The same is expected of the Branch Office, and woe to that manager who cannot do duty as a private soldier, and make his own office an example in all respects to the smallest " sub !" It were better for him that the General Manager had never been born ! The Canadian business is similarly managed from two Central Offices : one at Montreal, the other at Toronto. All these twenty-seven Central Offices report to New York, and receive their instructions direct from the officers of the Company. The London office has immense interests confided to its care, as before stated. The South American business is managed from London, principally because England enjoys facilities of communication with that continent which even Yankee enterprise has thus far neglected to secure for our own country.

36

37 (the picture of this page was relocated)

The business of Middle and Northern Europe and of Western Asia is managed from the Hamburg office, which, like the London office, makes a consolidated report to the principal office in New York. The total number of the Company's offices throughout the world is over 4.500, of which over one-third are in the United States. The foregoing are but a few of the interesting details of the organization and management of this remarkable Company, It is doubtful if any public or private corporation in the world can show so complete an organization. No bank is more scrupulously exact in every detail ; no army has a more systematic discipline. And while such a complete system is necessary to prevent so enormous a business, covering so much ground, from falling to pieces by its own weight, yet it is also true that the very completeness and compactness of this organization are themselves the best possible guarantees for the permanence and indefinite prosperity of this gigantic corporation.

38

39 (the picture of this page was relocated)

CHAPTER V

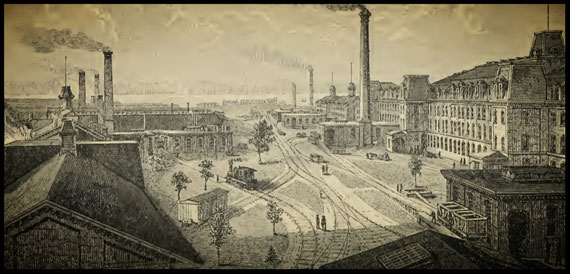

THE GREAT FACTORY

Our lady friends may like to know how and where the " Singer " was made which has done such valued service in their homes, and as it is a most natural desire, we are glad to be able to gratify the same. We, therefore, cordially invite all who feel disposed to come along while we take a hurried, but, we hope, interesting glance at the various parts of this mammoth workshop. Leaving the City of New York by the New Jersey Central Railroad, we dash through a dozen pretty Jersey villages, cross Newark Bay upon a bridge which lacks but a few feet of being two miles long, rush past the walls of the great Singer Factory, and alight at the Elizabethport Station, just beyond. This is one of the seven railroad depots of the beautiful City of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Looking back down the track, we see a finely laid-out park, with well-kept walks, handsome shrubbery and trees, and a profusion of flowers, in the centre of which stands a large fountain. This is the private park of the Factory, and is by far the handsomest in the city. The Singer Company bought an entire block in front of the Factory, and transformed it into a park which they maintain at their own expense. Beyond " Singer Park " loom, the massive proportions of the Singer Factory, four floors high, the upper story having a massive Mansard roof. The building is built of brick, iron and slate, with iron beams and girders, and is proof against those conflagrations which so often destroy human life in large manufactories.

40

The front is constructed of handsome pressed brick, and the structure is adorned with a tower in which a large clock shows the " hours as they fly " to all the neighborhood. Passing through the light and handsome offices, we find ourselves in what at first sight appears to be another park, shut in on three sides by long lines of high buildings. This is, however, not designed for a park, but is nothing more than the superbly-kept Factory Yard, embracing ten or twelve acres. Asphalt walks run down and across, connecting the various buildings that skirt the yard with each other, and with the dock at its foot. Beside and between the walks, every square foot of ground in this immense yard has been seeded with grass, whose green and well-kept borders are here and there fringed with shrubs and flowers. The walks are neatly kept, and though over two thousand workmen tramp daily through the yard, vve will not see a bit of dirt as big as a filbert anywhere.*

*(An amusing instance recently occurred in a Southern State of the use to which these grass plats could be put by persons whose tender consciences would not permit outright lying. A man interested in selling a cheap imitation " Singer," sent a letter to a Southern paper, enclosing a spear of grass which, he said, he '"had plucked in the yard of the Singer Factory," as evidence that the Singer Company was falling into decay, and its great factory being overgrown with grass and weeds).

41

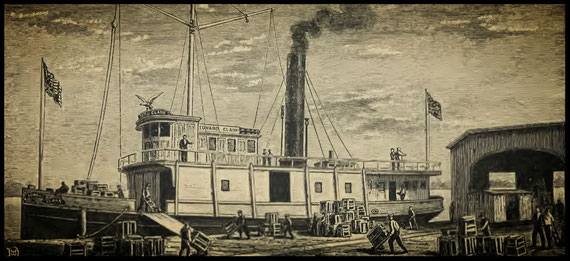

Up and down run railroad tracks from the main gate to the dock, with branch tracks to each shop door. These tracks aggregate over five miles in length, and are in constant use in bringing coal, iron, and lumber from the Central Railroad track outside, or the dock at the foot of the yard, or carrying car loads of machines to one or the other outlet. For this purpose the Company owns a locomotive, the " I. M. Singer," which puffs away busily at its work from morning till night. Here are long sheds, beneath which cars are being loaded with Singer machines for Chicago, St. Louis, or San Francisco. There are long trestles opposite the foundry doors, upon which coal cars, direct from Pennsylvania mines, are pushed by the "I. M. Singer," and their contents deposited "where they will do the most good." Iron, sand, and lumber cars are sent similarly to the exact spot where they are to be worked up, and so an immense cost of handling is saved. At the dock, which lies along Staten Island Sound nearly a thousand feet, the Company's steamer " Edward Clark," is taking on board a cargo of machines for New York City, or perhaps for some European steamship lying in New York Bay. Taking it for granted that all women are methodical, we must ask our fair visitors to go with us to the foot of the yard, and begin studying the manufacture of sewing machines just where the manufacturer is obliged to begin making them, at the foundry. Passing the great piles of pig-iron and the greater heaps of coal, we enter the foundries.

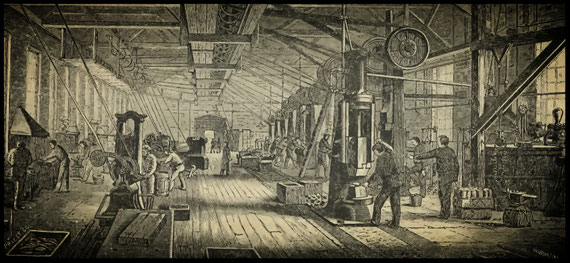

42

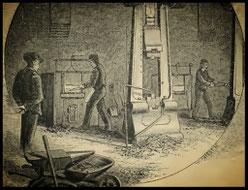

Upon yonder high platform two men are throwing great lumps of coal into the blazing, roaring mouth of a fiery furnace; and presently they stop throwing in coal, and begin to pitch in heavy bars of pig-iron, while the furnace hisses aloud with its fervent heat till it reminds us of Nebuchadnezzar's. At the foot of this furnace or "cupola" two or three men are catching the molten iron in a huge pot on wheels which,

43

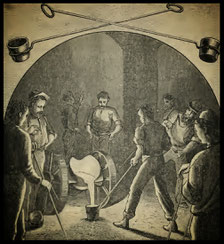

when full, is drawn to another part of the foundry, and there another lot of men surround it, their hand ladles are poured full, and away they hurry with their hot and heavy burden to fill the long rows of moulds which cover the floor. Four such cupolas are breathing out great blasts of fire at their tops, and running streams of fiery liquid iron at their bases. Three of them have a capacity for melting eight tons of iron each per hour, and the other converts six tons of pig-iron into liquid each hour.

44

The morning hours are occupied by the moulders in making moulds in sand of the various parts to be cast ; and for about two hours in the afternoon the cupolas send out their sparkling streams, and the men fill the molds with molten iron. When sufficiently cooled, the moulds of sand are knocked to pieces and the iron taken out and thrown into piles about the floor, while the sand is shoveled up and moistened for another day's moulding. Four hundred men are employed in this immense foundry, which melts up sixty-five tons of iron every day in the week. The ground floor of the foundry has an area of over two acres. Imagine a two-acre field filled every day with iron castings of Singer sewing machines ! And this is only a part of the iron work composing the machine. Much of the machine is composed of steel and wrought iron, which starts on its trip from the Forging Shop, instead of the Foundry. The portions cast in the foundry embrace the machine legs or " stands," the " arm " and "bed," the balance-wheel, band-wheel and a few minor parts. These parts, after cooling and being removed from the moulds, are taken to the Rumbling Room, 50 feet wide and 200 feet long, and put into revolving barrels filled with small five-pointed cast iron stars, which tumble about the barrels among the castings for hours together, and by the constant friction wear off all the sand and roughness.

The machine legs or stands then go to the Drilling Room, where the screw-holes are drilled out, and thence to the Japanning Room, where a set of grimy men, in half undress costume, souse them into a vat of liquid japan, after which they are put into great brick ovens, and left for several days for the japan to thoroughly bake and harden. This gives them a handsome, black, glossy finish and prevents rust. The other cast-iron parts are similarly treated, except the " arm " and "bed;" these, after being firmly secured together, are japanned and scoured down ; then japanned again, and again scoured down.

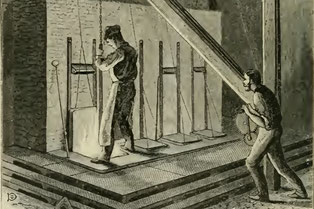

45

A third japanning and scouring is then given and they go to the Ornamenting Room, of which we shall see something shortly. The wheels, and other parts which work against other portions of the machine, go before japanning to the Milling Department, an immense shop 1,250 feet long, upon two floors, and 50 feet wide, where they are put upon a lathe and shaved off with steel knives to the exactness of a hair. Next above the Rumbling Room we come to the Forging Shop. Here numbers of great drop hammers are stamping out, at a single blow, the steel and wrought iron parts of the machines. These hammers weigh from three hundred to fifteen hundred pounds each. They are made with a "die" on their face, and the bed or anvil on which they drop has a corresponding die, so that a bar of hot iron held on the anvil is, by a single blow of the falling hammer, converted into a shuttle, a feed driver or a completely formed lever. Even the shuttle, which looks so much like a little boat, is made with a single blow of a huge drop hammer, which converts a square bar of iron in an instant of time into a perfectly formed shuttle. It is afterwards taken to another room, where another machine, with just one vigorous push, forces the shuttle through a sharp-edged aperture in a steel die, which trims off all unevenness and every bit of steel that may have projected beyond the edges of the die in the drop hammer. In another room the shuttle is drilled with holes for the thread ; in another it is polished on an emery wheel, and in yet another is fitted with the little check spring, and then, after receiving the bobbin, it is ready for service in your Singer machine.

46

The Forging Shop is 423 feet long and 50 feet wide. Leaving the Milling Department, each article is passed to the Inspection Department for "Parts", where every piece or "part" is examined and measured with an accurately made steel gauge and only such as are found to be exact and true to the thousandth part of an inch, are permitted to go on to the Stock Room.The rejected parts (and such is the accuracy of the machinery that these are comparatively few) go again into the furnace to be made over from the beginning. It is largely owing to the impartial rigidity of these inspections that the Singer machine has become so famous for evenness of work and for immunity from the periodical " fits " of misbehaving which so often afflict machines of other makes. And so the Singer Company makes no second grade articles, and puts nothing but the very best material and workmanship into any of its machines, finding, by practical experience, that it pays to put just as good parts into its cheapest as into the highest priced pearled and ornamented cabinet machine. Indeed, the only difference between the cheapest genuine Singer and the most costly machine is in the finish, decorations and cabinet work. All the working parts are exactly the same. The carefully inspected parts, after passing muster, are sent to the General Stock Room, where long rows of cases, extending nearly to the high ceiling, receive each sort into its appropriate box or shelf. Thence they are distributed in due proportions to the Assembling Department when called for.

47

The Stock Room is 50 feet wide and 180 feet long. Our fair friends will remember that we left the machine heads and bed plates in the Japanning Room, being scoured down after japanning. We must go back to them in order to keep up the connection. After being carefully scoured, the heads are sent to the Ornamenting Department, where skillful workmen pencil out, with a fine camel's hairbrush, the designs of flowers and scroll work which ornament that portion of the machine which rests upon the table. The rapidity with which these pretty and often intricate designs are traced is wonderful. Look at your machine at home ; observe all the gilded ornamentation and design, and then fancy a man doing such a machine head " off-hand," without the least guide for hand or brush, at the rate of 100 machines a day !

48

As quickly as the penciling is done the machine is seized by another man, holding in his hand a book of gold leaf, which he deftly lays over every pencil-line. The gold leaf firmly adheres to the "sizing" laid on by the brush and the rest is rubbed off by a single touch of another man who passes a piece of soft cotton batting over it. The whole is then varnished with the best quality of white varnish and placed in a huge oven, where it bakes till it has become perfectly dry, hard and glossy.

49

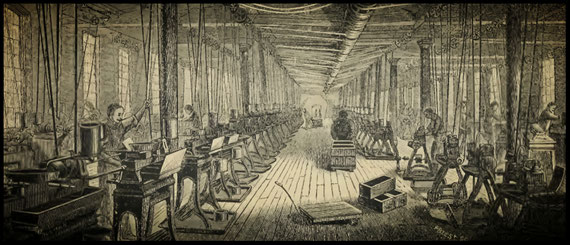

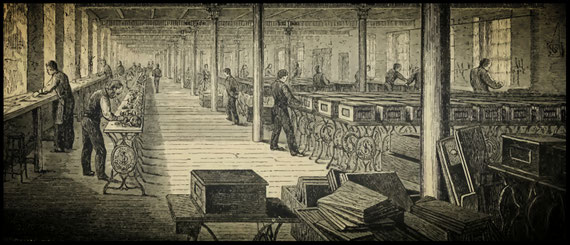

The Ornamenting Room is 125 feet long and 75 feet wide. The larger parts of the machine having now been japanned and ornamented, are brought to the "Assembling Room," and at the same time the small working parts are brought from the Stock Room, and here all these parts are "assembled," or brought together, and each placed in its proper position within or upon the machine head. Each of these parts has been so nicely fitted, and so accurately-worked by the machinery which made it, that when the numerous and varying pieces come together in the assembling process, it requires little and often no adjustment whatever, and each fits in the place made for it, resulting in a complete and harmonious whole. Connecting with this Department is the Adjusting Department, where long rows of machines on benches arc being run by steam at a very high rate of speed. This is yet another of the many testing processes through which your family " Singer " has gone in order to insure the absolute perfection of its working parts. Up and down these long rows of humming machines, skillful and patient mechanics are passing, narrowly watching each machine to see if it runs smoothly and properly. If a wheel revolves unevenly here, or a " bearing " pinches or is too loose there, back goes the machine to have the deficiency remedied, after which it must again pass the same ordeal.

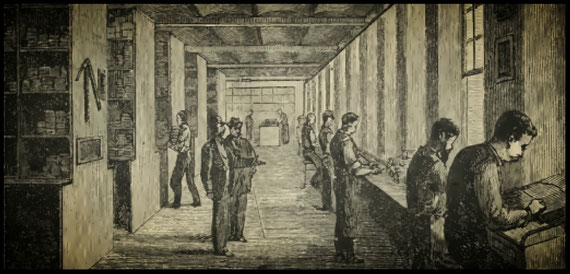

The Assembling and Adjusting Departments are 50 feet wide, and occupy a length of 1,100 feet on two floors. The views in these rooms cannot be adequately described, and we therefore give our readers accurate full page representations of the same. Next comes the Machine Inspection Department, 200 feet long and 50 feet wide. Here the machines are again inspected by competent artisans, and if perfect in every respect are passed over to long rows of girls, who put them through the further test of stitching, and see that they are capable of producing an absolutely perfect stitch. Over fifty girls are constantly employed in this particular work.

50

51

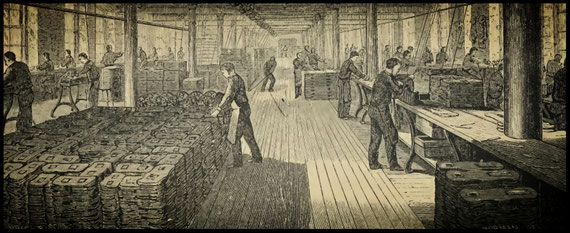

The next process is what is technically known as "setting up". The Setting Up Department is 460 feet long and 60 feet wide, and here the stands and tables are put together and placed in long rows ; the complete machine head is properly fastened in its place, the belts and treadle are adjusted, and the machine stands on its table ready for duty. Only one more operation is necessary for transportation, and that is packing or crating the machine.

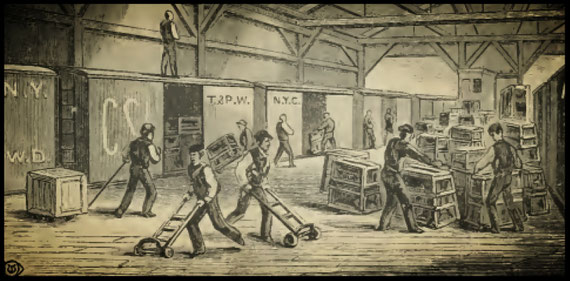

This is all done in the Shipping Department, which is 230 feet long by 60 feet wide. The boxes and crates have already been completely made up in the Box Shop, and nothing remains but to put the machine into the box or crate, as the case may be, drive three or four nails, mark the package with a Stencil plate for its proper destination, on New England's shores, on the great prairies of the West, amid the savannas of the South, or, perhaps, across the seas, lower it upon the elevator to the great shed, where it is loaded upon the cars. If its route lies via New York, it is placed upon a platform car, which the Company's own locomotive, the " I. M. Singer," draws to the dock to be shipped on board the Company's boat, the " Edward Clark."

A few parts of the machine require to be smoothly polished in order to secure the very best working capacity, and these are sent to the Polishing Room, which is a study of itself. Black wheels of all sizes are here revolving with great speed; some are rolling around on a horizontal axis, some are whizzing rapidly on a perpendicular axis, and from all of them the streams of fiery sparks are flying in unceasing currents, throwing the grimy room and the darkened forms of the busy workmen into a still darker background. This Department is 125 feet long and 50 feet wide. Another room is devoted to the manufacture of the steel springs used in the machine.

52

53

In another large department, 200 feet long, screws are being made by automatic machinery. In another room, loo feet long, the tools are made and repaired, and here a large force of skilled workmen is constantly employed. In still another room, filled with electro baths, the silver plated attachments are covered with their silver coats. The Button Hole Department is 150 feet long and 50 feet wide, and here the new Singer Button Hole Machine is put together. This is an intricate and wonderful piece of mechanism, by which an expert operator can make from 1.500 to 2.200 button holes a day, and sew the same thoroughly. This machine has but recently been introduced into general use, but has come rapidly into favor with manufacturers, especially tailors and makers of shoe uppers. It makes and works a complete button hole in either cloth or leather, and has come so extensively into favor that the Button Hole Department has outgrown its original quarters, and must be considerably enlarged. This, indeed, is true of almost every Department in the entire factory. When this great establishment was built, in 1873, it was thought a good week's work to turn out 4.000 complete machines ; but at this time its weekly product is upwards of 8.000 complete machines. Besides these, the Singer Company's other factory at Glasgow, Scotland, is turning out between 4.000 and 5.000 complete machines each week, and yet the offices throughout the United States and Canada are complaining of the injury their business receives because they cannot get enough machines. The factory at the time of writing is largely behind its orders. Enlargements of various departments have been made from time to time, but the demand is yet far ahead of the capacity for production.

The Needle Department is one of the most interesting features of the entire establishment. Here a coil of steel wire of fine quality is put into a machine, which straightens, then grooves it on both sides above and below the spot where the eye of the needle should be, and cuts it to proper length.

54

A girl then takes a handful of needles and, feeding them into a machine, punches the needle eye at a single blow. Then they are ground down to a point; after which they are tempered, and then the inside of the needle eye is polished out to prevent its cutting the thread. The whole needle is finally polished, and nothing more then remains but counting the shining bits of steel and packing them away in boxes for the trade. The Needle Department gives employment to 100 men and 50 women. Below the main building is a three-story brick building 200 feet long, in which the cabinet work is partly done. The Company has a large factory at South Bend, Indiana, where most of the black walnut tables, covers, and cabinet cases are made. Portions of these are sent to Elizabethport in a partly finished condition, and all such receive their finishing in this shop. Still below is another similar building, the " Box Shop," where some sixty men are employed in making the packing boxes and crates in which the machines are shipped from the factory. The Box Shop cuts up for this purpose no less than 300,000 feet of pine and spruce lumber every month. To run this immense establishment, six stationary steam engines are required, which have a combined strength of one thousand horse power. It takes twenty-two boilers, averaging seventy-five horse power each, to furnish the steam for running these engines and heating the buildings. The floors of the buildings have a combined area equal to thirteen acres of ground ; and every square foot of the entire area is in constant use. The whole premises, including the fine dockage, covers no less than thirty-two acres of ground. Such, in brief, is the factory where your Singer machine was made, dear reader.

55

It is believed to be the most complete, systematic, and best-equipped in the world. It is believed to be the largest establishment in the world devoted to the manufacture of a single article. It gives employment to over 2.300 men and women, and when it "shuts down" to take the annual account of stock, it takes 200 men to do it ; and this they call " shutting up the factory ! " The men are paid off every Monday, instead of every Saturday, and thus in more than one family the wife and children have had cause to bless the kind forethought which removed temptation from the path of some easily persuaded man, and saved him and his week's earnings to themselves. The Singer operatives are among the most thrifty of mechanics. In every case of injury to any of its employes, the Company has dealt with great generosity, and many are the households from which much of the black shadow caused by sickness has been chased by the substantial aid it has afforded. Nor do the hands leave this work alone to their employers.

56

Hardly a man is stricken by disease among their ranks but his comrades interest themselves in his case ; and if pecuniary aid is required, the subscription list goes around till every want is supplied at the sick man's home. These kindly offices are not confined even to these ample limits. When" the ghastly Yellow Fever Spectre was carrying dismay and death throughout the Southern States, the employes of this great factory made up, in less than four days, the splendid sum of $4.100, and sent it out on its errand of mercy to men whom they had never seen nor known. The factory hands have organized among themselves several very creditable associations. One is a fine Rifle Team, to which the Company contributed a handsome badge for an annual prize; another is a Brass Band of excellent reputation, besides several Ball Clubs having very good records.

CHAPTER VI

THE REASON WHY

There is a valid reason for everything in this world, whether we are able to find it or not, and for all this wonderful growth and Aladdin-like success there is a reason too. In 1872, when the great Chicago fire had impoverished thousands of the residents of that city, the Relief Committee undertook to furnish sewing machines to all the needy sewing-girls who might apply. Each girl was permitted to choose her machine from among the sixteen different kinds kept by the Committee. The total number of women who took machines was 2.944, and of this number 2.427 chose Singer machines, and the other 517 women distributed their choice among the fifteen

57

other kinds of machines. These poor women expected to earn their living on these machines, and there must have been some reason why such an overwhelming majority of them took "Singers" instead of machines of other make, each of which was loudly proclaimed by its manufacturers to be the "best in the world." The Singer Machines have been awarded the first premium over all others more than two hundred times, at great World's Fairs, at State Fairs, and at County Fairs in every part of the United States. As we have before stated, three-quarters of all the sewing machines sold throughout the world in 1879 were " Singers," and there must be a reason for that. When any one style of machine, used in millions of homes, leads all the other kinds to such an extent as that, there must be some way of accounting for it all, and if our readers choose to read on they will shortly discover why. An interesting fact in this connection was related to the writer recently by Mr. Galland, a large manufacturer of ladies' garments, whose factories are located at Scranton, Pennsylvania. The Gallands use several hundred sewing machines in their factories, operating them by steam. They had machines of many different makers originally, but gradually, as these machines wore out, had been replacing them with " Singers." The reason assigned was that they had noticed, from time to time, that when a Singer machine became vacant, the girls who worked on machines of other kinds were clamorous to obtain the Singer and leave their own ; and, when machines of other make were vacant, the girls were full of excuses for not taking them, but seemed desirous of waiting for the next vacancy, in hope of getting a " Singer." These observations led to inquiry from their master mechanic, who explained that the girls working on "Singers" lost less time in repairing, and in those

58

59

peculiar sewing machine " fits," than the girls who operated other machines. At this point the pay rolls were consulted by the inquiring proprietors, and there the whole secret lay exposed to view ; for the work was paid for by the piece, and the rolls showed that the girls operating Singer machines were earning from one dollar to two-and-a-half dollars a week more than the other operators ! Here then is the open secret of the Singer Machine's favor with the people. It is so simple that a child can understand it; it is so strong that a bungler can hardly get it out of order, and every part (as we have seen) is made with such scrupulous exactness out of the best materials, fitted in its place to the thousandth part of an inch, and tested and re-tested so many times before it is permitted to leave the factory, that it does not get the " fits " which try a woman's patience, destroy the fruits of her labor, and consume her time in vexing attempts to coax the machine back to duty. A gentleman wrote to the Company quite recently that he had a Singer Machine bought twenty-three years ago, and in use all that time, which sews perfectly to-day. Many people sit bewildered by the immensity of the Sewing Machine trade, and wonder what becomes of all the machines. The answer is very simple. If the trade is large, the world is larger still. Carefully prepared statistics show that the entire world contains at the present time not over six million sewing machines, good, bad, and indifferent. The United States alone contain nearly ten million families. But fully one million machines are not in homes but in factories, operated by steam, driven at the highest possible speed, and consequently wearing out in a few years. Therefore, if all the machines in the world were brought here they would supply only half the families of our own land. The civilized countries of the globe, where sewing

60

machines are now being introduced, have over seventy-million families, not including China, Japan and India, where a trade is being rapidly developed. In a word, the sewing machine is now being offered to a population of not far from a hundred million families, and the world contains not more than six per cent, of the number of machines necessary to supply them, without considering the enormous consumption of machines in shops and factories. It is plain, from these figures, that great as the trade has grown from the small beginning, it is yet in its infancy. Nevertheless, it has proved, except in a few instances, one of the most hazardous of enterprises. Probably as much money has been lost in the sewing machine business as has been made. The introduction of steam into manufactures and commerce has wrought changes so marked and rapid that none but keen and careful stvidents of their own times could keep track of them, and thousands of good men have gone down because they had not considered the new elements introduced, particularly into manufacturing industries, by steam and improved machinery. These have brought in a subdivision of labor which our forefathers scarcely dreamed about, and v/hich we have seen in our trip through the factory. It is almost incredible what speed a mechanic acquires whose task consists in performing one single brief operation, and repeating it over and over a hundred times an hour for months and years. We watched, with wondering interest, a man varnishing the under surface of the machine bed-plate. The space to be varnished was about a square foot in area, filled with obstructions and angles, every one of which must be touched with his brush. The operation was reduced to an exact science. His left hand caught the machine arm in just such a place every time ; his brush went into the pot in just such a way ; just so many sweeps it gave this way, exactly so many that way, and with precisely such a toss every time it was spun across the table to his assistant.

61

Spring and summer, fall and winter, that man did nothing but wipe that brush just so many times across that square foot of iron, and he did it with a precision and rapidity that was marvelous. The quickest painter we ever saw could not do one machine while he would finish five. And this is but a type of several hundred different operations into which labor is subdivided here, and which, by such subdivision, is so cheapened that employers whose capital and business will warrant it, can pay labor a good price and yet drive out competitors who are without large capital, large business and skill to use the advantages which are thus available.

62

On this rock many sewing machine manufacturers have split without, perhaps, knowing that it was only the lack of a large demand for their machines, and the absence of a large and well-directed capital which wrecked them. In the last few years over fifty sewing machine companies have failed, and swamped large nominal capital in the aggregate. The lesson is almost too obvious to justify the formulating of a prophecy that the sewing machine business of the future is likely to concentrate in a comparatively few corporations, whose skill, capital and facilities will be sufficient to bring out the best machines, made of the best materials; paying their skilled operatives liberal wages, and yet enabled, by this sub-division of labor, to offer them to the people at a price within the reach of all. Such is the story of the Sewing Machine from its paltry and inauspicious beginning. Such were the struggles and trials of the man to whose genius the world owes the vast, incalculable, and forever accumulating benefits of this great invention. And when we try to conceive what the world would be to-day if the Sewing Machine and all its concomitant blessings were suddenly removed from among its inhabitants, we look at this record of his achievements and rich triumphs, and rejoice that the common experience of inventors was not realized in the Sewing Machine invention, but that in this instance, at least, a great mechanician lived to see his Genius Rewarded.

63

from the book:

Genius Rewarded

As reproduction of historical newspaper articles and/or historical sources and/or historical artifacts, this works may contain errors of spelling and/or missing words and/or missing pages and/or poor pictures, etc.