- HOME

- Primary Sources

- The Invention of the Sewing Machine by Grace Rogers Cooper

- The Sewing Machine Combination or Sewing Machine Trust

- Vibrating Shuttle Sewing Machines History

- Running-Stitch Machines

- Button-Hole Machines

- Book-Sewing Machines

- Glove-Sewing Machines

- Shoe Making Machines

- Needles

- Shuttles & Bobbins

- Bobbin Winders

- Thread Tension Regulators

- Feed Reversing Mechanism

- Attachments and Accessories

- MANUFACTURERS AND DEALERS IN SEWING MACHINES

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

- PATENTS

- DATING FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- FRISTER & ROSSMANN

- BRITISH Machines

- BRITISH Machines Part 1

- BRITISH Machines Part 2

- BRADBURY & Co.

- BRITANNIA SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BRITISH SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Ltd

- ECLIPSE MACHINE COMPANY

- ESSEX

- GRAIN E. L. Ltd

- W. J. HARRIS & C0.

- IMPERIAL SEWING MACHINE CO.

- JONES & CO.

- LANCASHIRE SEWING MACHINE Co

- SELLERS W.

- SHEPHERD, ROTHWELL & HOUGH

- VICKERS

- WEIR'S

- AMERICAN Machines

- AETNA SEWING MACHINE

- AMERICAN B.H.O. & SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AMERICAN SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- AVERY SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTHOLF SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTLETT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- BARTRAM & FANTON Mfg. Co.

- BECKWITH SEWING MACHINE Co.

- BOYE NEEDLE COMPANY

- BURNET, BRODERICK & CO.

- CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURING Co.

- DAVIS SEWING MACHINE CO.

- DEMOREST SEWING MACHINE MANUFACTURING CO.

- DOMESTIC SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- DORCAS Sewing Machine

- EMPIRE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- EPPLER & ADAMS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- GOODSPEED & WYMAN S.M. Co.

- GREIST MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- GROVER & BAKER SMC

- HEBERLING RUNNING STITCH GUAGING MACHINE Co.

- HIBBARD, SPENCER, BARTLETT & Co.

- HODGKINS MACHINE

- HOWE MACHINE COMPANY (Elias)

- HOWE S. M. C. (Amas)

- N. HUNT & CO.

- HUNT & WEBSTER

- JOHNSON, CLARK & CO.

- LEAVITT & CO.

- LEAVITT SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- LEAVITT & BRANT

- LENOX MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- NETTLETON & RAYMOND SEWING MACHINES

- NEW HOME SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- NICHOLS & BLISS

- NICHOLS & Co.

- NICHOLS, LEAVITT & CO.

- REMINGTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- REECE BUTTON HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- SINGER

- SMYTH MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- UNION BUTTONHOLE and EMBROIDERY MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON-HOLE MACHINE COMPANY

- UNION BUTTON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- TABITHA Sewing Machine

- WARDWELL MANUFACTURING COMPANY

- WATSON, WOOSTER & Co.

- WEED SMC

- WHEELER & WILSON

- WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- WILLCOX & GIBBS

- WILSON SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

- CANADIAN Machines

- GERMAN Machines

- Deutsche Nähmaschinen-Hersteller und Händler

- Development in industrial sales

- About innovations on sewing machines

- Bielefeld Nähmaschinenfabriken

- Nähmaschinen in Leipzig

- ADLER

- ANKER-WERKE A.G.

- BAER & REMPEL

- BEERMANN CARL

- BELLMANN E.

- BIESOLT & LOCKE

- BOECKE

- BREMER & BRÜCKMANN

- CLAES & FLENTJE

- DIETRICH & Co.

- DÜRKOPP

- GRIMME, NATALIS & Co.

- GRITZNER

- HAID & NEU

- HENGSTENBERG & Co.

- JUNKER & RUH

- KAISER

- LOEWE & Co. / LÖWE & Co.

- MANSFELD

- MÜLLER CLEMENS

- MUNDLOS

- OPEL

- PFAFF

- POLLACK , SCHMIDT & CO.

- SCHMIDT & HENGSTENBERG

- SEIDEL & NAUMANN

- SINGER NÄHMASCHINEN IN GERMANY

- STOEWER

- VESTA

- WERTHEIM

- WINSELMANN

- ITALIAN Machines

- HUNGARIAN / MAGYAR Machines / Varrógépek

- AUSTRIAN Machines

- BELGIAN Machines

- FRENCH Machines

- RUSSIAN Machines

- SWEDISH Machines

- SWISS Machines

- NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS

- 1850 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1850 BOSTON

- 1851 LONDON

- 1851 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1852 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1853 BOSTON

- 1853 DUBLIN

- 1853-4 NEW YORK

- 1854 MELBOURNE

- 1855 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1855 PARIS

- 1856 BOSTON

- 1856 NEW YORK - FAIR

- 1860 STUTTGART

- 1861 MELBOURNE

- 1862 LONDON

- 1866 ALTONA

- 1869 BOSTON

- 1873 VIENNA World Exhibition

- 1876 PHILADELPHIA

- 1884 LONDON Health Exhibition

- 1884 LONDON International and Universal Exhibition

- 1885 LONDON South Kensington Exhibition

- 1887 LONDON American Exhibition

- 1889 PARIS Exposition Universelle

- 1893 LONDON The Sewing and Domestic Machines' Show

- CURIOSITIES

- READING ROOM

- SEWING MACHINE MUSEUMS - Links

- USEFUL LINKS

Room 17

EXTRACT FROM

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF AMERICAN COMMERCE

CONSISTING OF ONE HUNDRED ORIGINAL ARTICLES ON COMMERCIAL TOPICS DESCRIBING THE PRACTICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE VARIOUS BRANCHES OF TRADE IN THE UNITED STATES WITHIN THE PAST CENTURY AND SHOWING THE PRESENT MAGNITUDE OF OUR FINANCIAL AND COMMERCIAL INSTITUTIONS

1795-1895

AMERICAN SEWING MACHINES

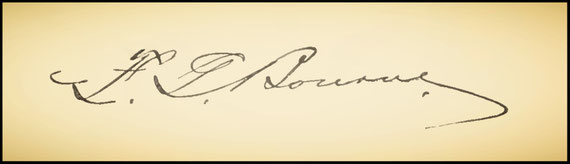

by Frederick G. Bourne, New York

President The Singer Manufacturing Company

The American sewing machine is the sewing-machine of the world. Not only is this true as to the machines used for domestic purposes, but of machines used in manufacturing for stitching all kinds of textile fabrics and leather, including special machines for working buttonholes, eyelets, overseaming, embroidery, etc. It is, however, proper, in writing a brief history of the inception and invention of the sewing machine from its beginning down to the advent of the first American sewing machines which were of practical value as an article of commerce and trade, that we refer to what had been done in other countries in the way of inventing and producing sewing machines.

The first sewing machine of official record is that of Thomas Saint, on which a patent was granted in England, July 17, 1790. It is not known whether more than an experimental machine was made; only the drawings on file in the English Patent Office, together with a full description of the machine in the specifications of the patent, are in evidence to show to what extent success was attained. Enough is shown in the drawings and description to demonstrate that it corresponded more nearly to the form and mechanical arrangement of the first successful American productions of 1850 than did any of the several machines made during the intervening time.

Knight says in his "Mechanical Dictionary": "The overhanging arm, vertically reciprocating needle, continuous thread and automatic feed, were patented in England fifty years before Greenough's (machine) and sixty years before the Singer attained its excellence".

This indicates that subsequent inventors from 1790 to 1850 either did not have knowledge of Saint's invention or did not choose to profit by it.

The first sewing machine of official record that was put into operation is that of Barthelemy Thimonnier, patented in France in 1830. This machine was so far a success that in 1841, it is said, eighty of them were made and used in making clothing for the French army and were destroyed by a mob, as had been the Jacquard loom and other labor-saving machines years before. Thimonnier made another attempt in 1848 to introduce his machines in France and a mob again defeated his efforts. He took out a patent in the United States, September 3, 1850, but his machine had no important features that were of value as compared with the sewing machines of that date.

Several patents on sewing machines were taken out in England and the United States up to the year 1846, but none of them contained the essential features necessary for success.

September 10, 1846, Elias Howe, Jr., took out a patent in the United States on a machine that had new and important features and that placed his name among the great inventors of this age of inventions. Prior to Howe all the sewing machines patented made the chain or tambour stitch, or attempted to imitate sewing by hand, making what might be called the backstitch. They used a short thread with a common needle that was passed through the material and pulled out with pincers, or else a needle with an eye in the center, passing it through the material and making the same stitch as is common to workers in leather. The chain-stitch was produced by Saint, Thimonnier and others and might properly be called a knitted stitch, as they used a continuous thread direct from the ordinary spool and the stitch was formed the same as in knitting. Howe used an eye-pointed needle and a shuttle, passing the shuttle through a loop of the needle-thread and producing a lock-stitch alike on both sides of the material, with the lock or intertwining loops of the two threads pulled to the center; this might very appropriately be called a woven stitch in contradistinction to the chain or knitted stitch. There is a general impression that Howe invented the eye-pointed needle, but this is not true. The eye-pointed needle was invented many years before and was extensively used in France for the purpose of working by hand, in a chain-stitch, the name of the manufacturer on the ends of broadcloths. It was also used in chain-stitch sewing-machines. Howe's invention consisted of the combination of the eye-pointed needle with a shuttle for forming a stitch and an intermittent feed for holding and carrying the material forward as each stitch is formed. The mechanical device for the feed was called the "baster-plate" and the length of the seam sewed at one operation was determined by the length of this plate. The material to be sewed was hung by pins to the "baster-plate" in an upright position and if the seam to be sewed was of greater length than the plate it was necessary to rehang it on the plate, which was moved back to position in the same manner as a log is carried back and forth in a saw-mill. It is not claimed that any machines made after the model of the original Howe machine were ever put into practical use. Mr. Howe, in his application for an extension of his patent, only claims to have made three machines, one being the model deposited in the United States Patent Office and the other two he retained and claims to have used in sewing the seams for two suits of clothes, one for himself and the other for Mr. Fisher, the assignee of one half of the patent. Mr. Howe also relates that, not meeting with any success in obtaining adequate capital in this country, he sold the other half of his patent to his father for $1.000 and went to England, where his right for a patent had been sold to William Thomas for £250. He engaged to work for Mr. Thomas at £3 per week in perfecting and adapting the machine for work in the corset factory of Mr. Thomas, in London. He was not successful in this and was arrested for debt and took the "poor debtor's oath". Through the kindness of the captain of an American packet he was enabled to send his wife and children back to the United States. Later he took for himself steerage passage for Boston, where he found that sewing-machines had been made during his absence that infringed his patent. He then obtained a reconveyance of the half-interest previously conveyed to his father and commenced suits to enforce his rights in Boston and New York. In the latter city he found I. M. Singer & Company making and selling machines, they setting up in the courts, in justification of their right to make machines, the claims of Walter Hunt, who established the fact that he made a sewing-machine with an eye-pointed needle and a shuttle that made the lock-stitch previous to the year 1834, but failed to apply for a patent on it or to produce a machine made at that time. Mr. Howe further says that the suits brought by him in New York were fought with the utmost vigor and pertinacity by I. M. Singer & Company but the courts decided that Hunt's invention was never completed in the sense of the patent law and did not in any way anticipate the patent granted to Howe. I. M. Singer & Company submitted to the decree of the court and July 1, 1854, took out a license under the Howe patent and paid him $ 15.000 in settlement of license on machines made and sold prior to that time. Howe then purchased the other half-interest of his patent and his success in the Singer suit made it comparatively easy for the enforcement of his legal rights with others. He obtained an extension of his patent in 1860 for seven years and again applied for another extension in 1867, setting up that he had received only $1.185.000, that his invention was of incalculable value to the public and that he should receive at least $150.000.000 for it. His second application was very properly denied.

In 1853 Amasa B. Howe, an elder brother of Elias Howe, Jr., commenced the manufacture of sewing-machines under a license from his brother Elias, in which he infringed the Bachelder, Wilson and Singer patents. Under subsequent arrangements he obtained the right to use those patents and the machines were called the "Howe sewing machine". This gave an erroneous impression to the general public as to what was really the original Howe sewing machine. The facts in regard to it came out in after years, when Elias Howe, Jr., made an attempt to manufacture sewing-machines that were very like those made by Amasa B. Howe and endeavored to appropriate the name of Howe as a trade name for the machines he manufactured. A suit brought by Amasa to establish his right to the word "Howe" as a trade name proved successful, the decision of the court being that Amasa B. Howe was the original inventor and proprietor of the trade-mark of "Howe" as applied to sewing machines.

The next invention patented that covers a fundamental and important feature was that of John Bachelder, patented May 8, 1849. Bachelder's machine was the first to embody the horizontal table with a continuous feeding device that would sew any length of seam. His invention consisted of an endless leather belt set with small steel points projecting up through the horizontal table and penetrating the material to be sewed, carrying it along intermittendy at a proper time to meet the action of the needle.

To Allen B. Wilson must be awarded the highest meed of praise as an inventor and for the ingenuity displayed in constructing and improving the sewing machine. His patent of November 12, 1850, covered the invention of the moving feed-bar, with teeth projecting up through the horizontal table or plate of the machine, in conjunction with a presser-foot coming down on the material to be sewed and holding it in position for the action of the feed-bar. His patents of August 12, 1851 and June 15, 1852, for improvement in a feeding device and for a revolving hook for passing the upper thread around the bobbin containing the under thread, gave to the world a feed that would admit the sewing of a curved seam, which has become almost universal in the sewing-machine, while the revolving hook is a marvelous piece of ingenuity and mechanical skill. It is to be regretted that Wilson did not receive an adequate reward for his great inventions. In his petition to Congress in 1874 for a second extension of the three above-named patents he stated that he did not receive anything above his expenses during the fourteen-year term of his original patent; that owing to his impecunious condition he was obliged to sell a half-interest for $200; that for the seven years term of the extension he had only received $137.000 and that he had no stock or interest in any company manufacturing sewing machines at that date; which statements were verified by his original partner. The sewing machine constructed by Allen B. Wilson was small and light and only adapted for domestic purposes in the ordinary sewing for a family, or on very light fabrics in manufacturing. It used a vibratory arm for carrying the eye-pointed needle, which was curved to meet the arc of the circle described by the motion of the arm.

In 1873 the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company produced its first machine, with horizontal bed and overhanging arm attached thereto, using a needle-bar with perpendicular action and carrying a straight needle. Its vibratory arm was actuated by a cylinder-cam on the shaft under the table of the machine. This defective and cumbersome mechanism was not a success and was superseded by a rockshaft in the overhanging arm. This was again displaced by substituting the revolving shaft, as used in the original Singer machine and giving motion to the needle-bar and the upper thread "take-up" in the same manner as applied on the Singer machines at the present day.

In 1850 Mr. Isaac M. Singer visited Boston for the purpose of promoting the manufacture of a machine that he had invented for carving wood. His attention was there called to a sewing-machine made by Blodgett & Lerow, after the model of the Howe machine. That night he worked out in his mind a machine differing materially in shape, form and mechanical construction and made a rough draft of his conception, showing its advantages over the plan of construction of the first and only sewing-machine he had ever seen or heard of. The feasibility of his plans being apparent to Mr. Orson C. Phelps, the owner of the machine-shop and to Mr. George B. Zieber, who had previously been interested in the machine for carving; an agreement was entered into by which Singer was to furnish the plans, Phelps to do the work in his shop and Zieber to put in $40 in money to pay for materials and expenses. It is a matter of well-authenticated history that the first machine was made in eleven days and that "it went to work at once" and was the most perfectly organized sewing machine for practical use that had been made up to that time. Thus was created a sewing machine that in its size and the mechanical construction of its arm and table serves as model for ninety-five per cent, of all the sewing machines that are being made throughout the world to-day. It had the horizontal table, with a continuous feeding device coming up through an aperture in the table; an overhanging arm attached to the table; a horizontal shaft in the arm giving motion to a needle-bar acting perpendicularly and carrying a straight eye-pointed needle; a horizontal shaft under the table of the machine and directly connected with and driven by the upper shaft, giving proper motion for moving the shuttle back and forward and an intermittent motion to the feedwheel, which was an improvement over the Bachelder feed, as it was constructed of iron, with a corrugated surface that did not penetrate the fabric or injure its surface. It also had a presser-foot to hold the fabric down to the feed-wheel, which had a yielding spring that would permit of passage over seams, or would sew different thicknesses without requiring any change in its adjustment. This important feature had not been shown in any other machine up to that time. The yielding spring presser-foot was claimed by Mr. Singer in his original application for a patent on a sewing machine but this claim was disallowed because there was a question as to who was the first to invent this important feature, although the idea was undoubtedly original with Singer. The construction of the original Singer machine, with its straight horizontal shaft in the overhanging arm, easily admitted enlargement and extension, thus gaining increased space for handling the work. As an indication of its capabilities in this respect it may be stated that at this time there are over forty distinct classes of machines made by The Singer Manufacturing Company, that vary in size and capacity from the smallest for domestic purposes to a machine having a bed eighteen feet in length and capable of stitching canvas belting of any practicable width and up to one and one half inches in thickness. Mr. Singer did not confine his efforts to his original machine and the lock-stitch, but in 1854 he invented a "latch underneedle" and constructed a machine making the single-thread chain-stitch and the same year he produced a machine for embroidering, using two threads and making a double-thread chain-stitch, with a very ingenious mechanism for throwing another thread back and forth in front of the needle and producing an ornamental fringe. In 1856 he brought out a machine making the lock-stitch, but discarded the wheel-feed and used the "Wilson four-motion feed" so that the name of Singer, as applied to sewing machines, did not designate any particular type of machine, or a machine making any one kind of stitch, or using either of the well-known feeding devices. He also turned his attention to making attachments for the sewing machine, in the way of binders, rufflers, etc.

The machines of prior date to Singer and many of them for a long time after, used either a vibratory arm and a curved needle or a vibratory arm and a needle-bar carrying a straight needle. It is obvious that a machine constructed on either of these principles could not be enlarged without destroying its effectiveness. The shorter the arm, the greater the curve of the needle and the more contracted the space for turning and handling the work; the longer the arm, the more liability to spring and affect the proper action of the needle and the more power required to propel the machine and drive the needle through the material to be sewed.

We have now reached a period where the inventors had discovered the essential features of a sewing machine and made them mechanically practicable.

The time had arrived for active and practical business men to take hold of it and make the discovery of value to the world at large. A new industry had sprung into existence, the product of which was not only to be of great importance in itself, but was also to work a revolution in many branches of manufacturing industry.

The men who came to the front and duly appreciated the magnitude of the prospective business were Mr. Nathaniel Wheeler of the Wheeler & Wilson Company, Mr. Orlando B. Potter of the Grover & Baker Company and Mr. Edward Clark of I. M. Singer & Company. Mr. Nathaniel Wheeler became a partner of Allen B. Wilson in 1851. Mr. Wheeler brought with him energy and ambition that soon developed into superior business ability. This, with fine presence and engaging manners, enabled him to obtain financial aid from some of the leading capitalists of Connecticut, his native State. His great tact in the way of bringing before the public, by advertisements and otherwise, the fact that sewing by machinery could be practically accomplished in the household gave the invention of Wilson an enormous sale and its manufacture at Bridgeport, Conn., soon became one of the most important manufacturing industries in that city.

Mr. Wheeler became prominent in banking and other business interests and received political honors from both city and State. He was president and general manager of the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company from its organization down to the date of his decease, in January, 1894 (December 31, 1893).

Mr. Orlando B. Potter was president of the Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company, a corporation organized under the laws of Massachusetts, with its factory located at Boston. Mr. Potter, however, recognized the fact that New York was the metropolis and the proper place for him to establish himself and the headquarters of his company. The inventions of William O. Grover and William E. Baker were of prime importance in some of the sewing machines of early date, but the great feature was the "Grover & Baker stitch". It was formed by interlocking the upper and lower threads on the underside of the material and producing on the knitting principle a double chain-stitch. This company also made a few machines using a shuttle and making the regular lock-stitch but Mr. Potter became imbued with the belief that the Grover & Baker stitch would be the stitch universally used in family sewing and nearly every branch of manufacture and he apparently directed his efforts to that end. That he had committed an error became evident, as the sales of the Grover & Baker machines decreased, while those making the lock-stitch were increasing in much greater proportion. In 1875 Mr. Potter sold out the business and all the effects of the Grover & Baker Sewing-Machine Company to a company making lock-stitch sewing machines. The demand for the Grover & Baker machines became so small that their manufacture soon ceased and the name of the Grover & Baker machine and stitch soon passed out of existence.

The merits of a double chain-stitch are in its elasticity and in using the under thread direct from the commercial spool without rewinding. Machines making a similar stitch have been made since that time for use in the manufacture of knit goods, bags, etc., where an elastic seam is required and the stitch is also used in machines made by the Singer Company for sewing the seams in carpets.

After Mr. Potter's graceful retirement from the sewing machine business he showed his faith in the progress and growth of his adopted city. New York, by large investments in real estate. He became interested in politics, being twice elected to Congress, where he was very prominent and an important member of some of its leading committees. The complex and important litigation of the early days of the sewing machine required the employment of the very best legal talent of that period and soon after the establishment of the business of I. M. Singer & Company in New York, in the early part of 1851, they employed Messrs. Jordan & Clark as their attorneys and counselors. The senior member of that firm, Ambrose L. Jordan, was at that time attorney-general of the State of New York and the affairs of that office so engrossed his attention that the junior partner, Edward Clark, took in charge the new clients. They were unable to pay the fees and costs of the extensive litigation in which they were involved and Mr. Clark accepted an interest in the firm to secure payment for his services and the advances he had made. Mr. Singer recognized the legal ability and business sagacity of Mr. Clark and proposed that they should buy out the interest of the other partners, Mr. Clark taking charge of the legal and financial branch of the business, while Mr. Singer gave his attention to the manufacturing and improving of the sewing-machine. In March, 1852, they consummated this arrangement and from that time up to the incorporation of The Singer Manufacturing Company, in April, 1863, Mr. Clark had charge of the financial and commercial branch of the business and directed the affairs in litigation. That he conducted both of these important parts of the business with success is well attested by the remarkable growth of the first and the well-protected interest of the latter. Mr. Clark at an early day appears to have fully comprehended the value of the sewing machine as an article of trade and commerce. His policy always contemplated the diffusion of the business in every direction, following the most direct method of placing its products in the hands of the consumer. He not only established agencies throughout the United States, which were conducted by agents employed under salaries, but he gradually extended a system of agencies throughout Europe and all other parts of the civilized world. In 1856 he originated and inaugurated the system of selling sewing machines on the renting or instalment plan and this method has been adopted and extended throughout the offices of the company all over the world. This system has been extended by others to the sale of nearly every article of merchandise, from a family Bible to a railway-car and has proved of inestimable benefit to mankind.

Mr. Clark continued to take an active interest in the business of The Singer Manufacturing Company, holding the office of president of the company from 1876 down to the day of his decease, in 1882. He was a large owner of real estate in the city of New York, being one of the first to construct a building for residences on the French system. Among the notable buildings of this class erected by him are the "Dakota" and the "Van Corlear". Mr. Clark was of a very modest and retiring disposition and never permitted himself to be brought prominently before the public and although he was at the head of one of the largest mercantile enterprises in the world, his natural tendency for association was with the members of his profession. If occasion called he had an easy flow of rhetoric and with a pen his diction was pure, terse and to the point. These qualities, with clear logical reasoning on legal questions and an inherent love of equity, would have insured him high standing had he continued in active practice at the bar, or he would have graced with ornate dignity the bench of a court of last resort.

After the validity of the patent of Elias Howe, Jr., had been fully established, he commenced a system of licenses to manufacturers of sewing machines, demanding the exorbitant price of $25 on each machine, without any regard to its merits. In his application for a second extension of his patent he states that his first license was granted May 18, 1853 and that up to July, 1854, he had granted fifteen licenses "for the general manufacture and sale of sewing machines". As Howe's imperfect and impractical models did not contain the features essential to practical sewing machines, the result of operation under his licenses was suits and countersuits by the owners of the more important patents and great distrust and unrest on the part of all purchasers of sewing machines.

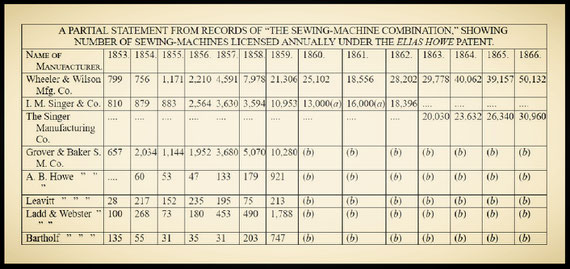

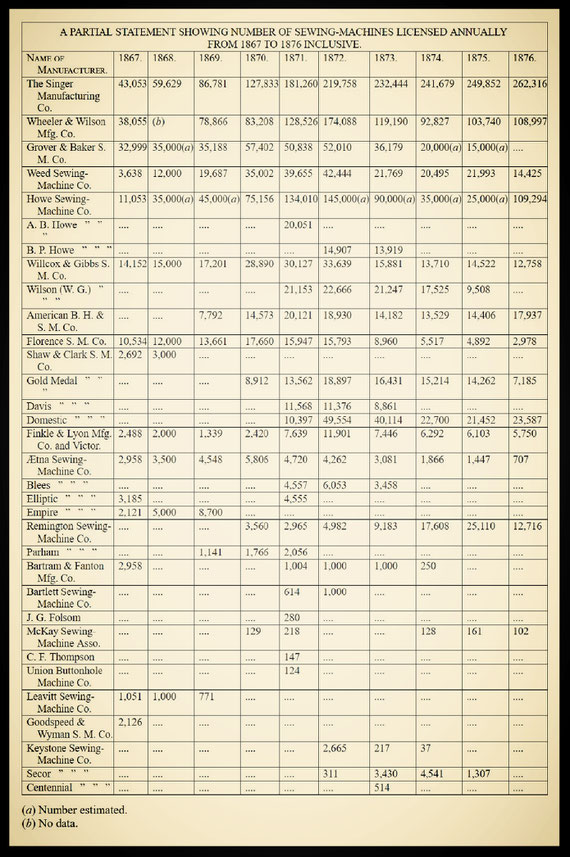

In 1856 the owners and controllers of the Bachelder, Wilson and other fundamental patents brought about a coalition, in which they included Elias Howe, the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company, the Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company and I. M. Singer & Company; thus forming the famous "sewing machine combination" in which were pooled all the patents of the essential features of the sewing-machine in such a way as to protect the interest of each of its members in an equitable manner and enable other manufacturers to continue in the business by the payment of only one license-fee to the combination. Under this arrangement any manufacturer who had a meritorious machine that was not an offensive imitation of the machine of some other licensed manufacturer was granted a license, the rate being uniform to all and much less than the excessive and exorbitant license previously demanded by Elias Howe, Jr. There was no pooling of any other interest in the combination excepting that of the patents; no restrictions were placed on the price at which the machines were to be sold, either at wholesale or retail, but the market was open to fair competition on the merits of the several machines and the result was to be the "survival of the fittest". The combination continued in existence with Mr. Howe as a member until the expiration of the extended term of his patent in 1867 and was then continued by the other members in interest until the expiration of the Bachelder patent in 1877. No record or estimate was made as to the number of sewing machines manufactured prior to the date when Howe began to grant licenses, but from that time to the termination of the combination a report was made at stated periods by all licensed manufacturers. Unfortunately some of the records of the combination were destroyed by fire and only a partial list, showing the number of machines made from 1853 to 1877 by each of the several manufacturers, can be furnished. Enough, however, is shown in the tabular statement appended to indicate the volume of business from year to year during that period.

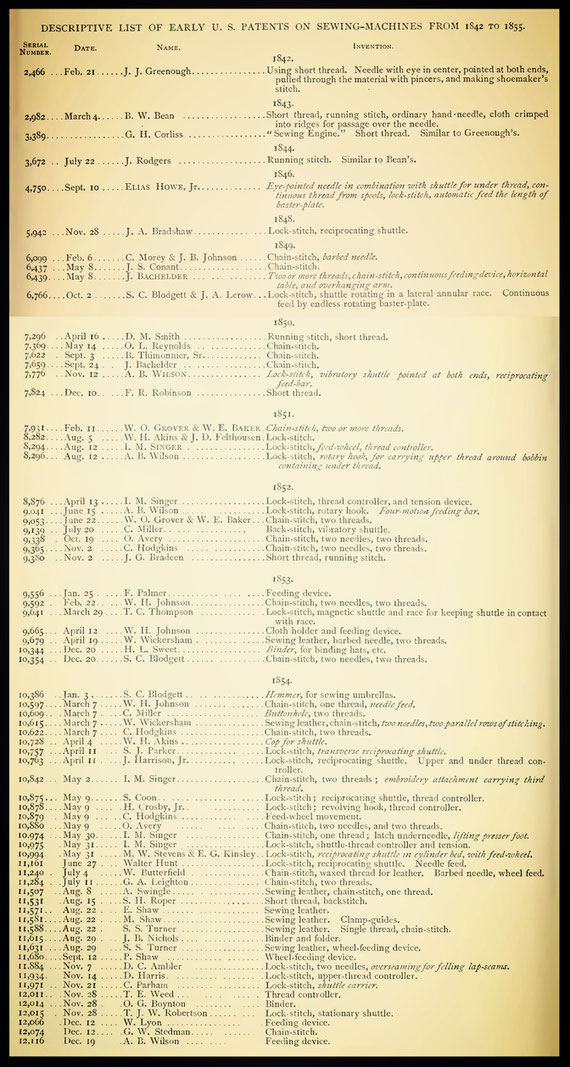

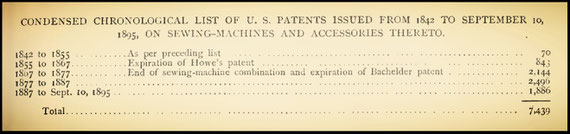

From the beginning to the end of the combination there was an army of would-be infringers and imitators who kept up a constant howl on any and all occasions, claiming that the existence of the combination tended to retard the improvement of the sewing-machine and that the public were the sufferers thereby. It is now nearly twenty years since the expiration of the last important patent on a fundamental principle of the sewing machine and it is a notable fact that two of the companies that were members of and formed the combination in 1856 are the only manufacturers, with one or two exceptions, that have shown any marked improvement in the sewing machine proper over those of twenty-five years ago, or who now produce machines that are capable of being run by steam or other power at the high rate of speed and doing the grade of work, that is required in the factory use of sewing machines at the present day. It may be said that the patents issued to Howe, Bachelder and Wilson cover all the fundamental principles of the sewing-machine. If we divide the various machines into two classes, the "dry thread" and the " wax thread," it appears that the number of patents covering all the essential elements in the first-named class do not exceed ten and an equal number those in the other. Reference will be made later to important inventions in machines using wax thread and only employed on leather in the manufacture of boots and shoes, harness, etc. The inventive genius of the age is actively engaged in the production of new developments of the sewing-machine and patents covering devices of more or less utility are constantly being granted. The annexed list shows the number of patents issued by the United States for sewing machines and accessories, from the first to J. J. Greenough, dated February 21, 1842, down to September 10, 1895, the total being 7.439. Of this number there were:

Sewing-machines making the chain-stitch .............................................. 433

Sewing-machines making the lock-stitch .................................................661

Sewing-machines for stitching leather .....................................................431

Feeding devices for sewing-machines ......................................................316

Machines for working buttonholes ...........................................................448

Machines for sewing on buttons ...............................................................33

Miscellaneous parts of sewing-machines ...............................................2.950

Attachments, rufflers, hemmers, corders, etc ........................................1.524

Cabinet cases and tables .......................................................................473

Motors: foot, hand, steam, air and electric ...............................................170

This classification is a continuation in part of the system adopted and used in Knight's " Mechanical Dictionary", comprising patents on sewing machines issued up to March 10, 1875. It is not a complete or accurate classification, as it enumerates each patent only once, classifying it according to its most important feature, although it may cover several other minor features of the sewing machine which may have been embodied in the same patent. For instance, the original Howe patent covers the combination of the eye-pointed needle and the shuttle for forming the stitch and also the very important device for feeding the material to meet the proper action of the needle and shuttle; yet it is entered in the list but once and then simply as a sewing machine making the lock-stitch.

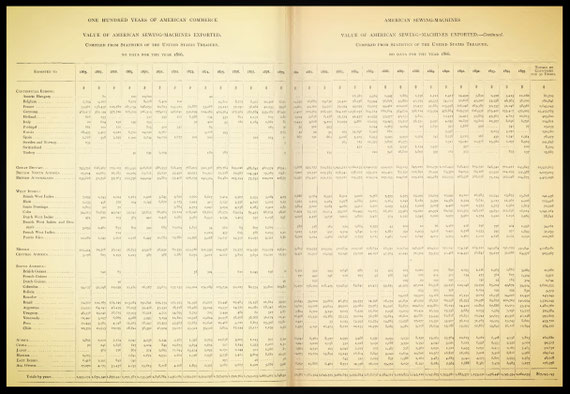

The large number of patents indicates that inventors have not been idle or neglected the sewing machine. But there is something required aside from the mere invention. The inception of the original idea is only the first essential; it is equally necessary to have the place and opportunity to experiment and to get the machine into practical operation and test it on the class of work it is required to do. In the larger factories of the present time the experimental department is one of the most important and expensive. Here the inventor's idea is carefully wrought into form and receives preliminary tests of its efficiency. After carrying it to what seems to be a perfect condition, involving months and sometimes years, of patient toil and disappointment, the machine or attachment is then sent to various factories engaged in the class of work for which it is intended and there it is put to the severest tests of practical use. If its operation appears to be satisfactory, then a special plant of machinery is installed to make this new machine, attachment or part, so that it can be perfectly duplicated in any number required. After all this expensive preparation and experiment, the invention may soon be replaced by something better and be abandoned. Notable instances of this are shown in the development of the Goodyear machine for stitching soles to shoes. It was a matter of several years of devoted labor before the inventors succeeded in getting this machine to perform satisfactory work and within the past year improvements have been made that render a change from the old to the new machines desirable. The same can be said of the latest production of the Singer Company for sewing breadths of carpet together. The older machine is propelled by hand-power and the operator walks along by the side of the distended breadths, working the machine and using some skill and labor in getting the carpet properly matched and stretched. The new machine is operated by mechanical power and is constructed so as to hold the carpet in position by means of clamps, that also assist in matching the figures properly and then stretch it so that it will lay perfectly flat on the floor after it is sewed. The little sewing machine, which passes along on a track in proper position to do the sewing, is propelled by electric or other power. It starts and stops by means of automatic devices that work in conjunction with the clamps that match and hold the carpet in position. When it arrives at the end of the seam it unlocks itself from the forward motor-power and grasps another, that takes it quickly back to place of beginning. The production of the hand-machine is equal to that of eight or ten hand-sewers; but the new power-machine has a capacity eight or ten times greater than the hand-machine and one operator can handle the increased quantity of carpet with greater ease and less labor. There is no royalty on the product of this machine, but it is sold outright, as are all machines made by the Singer Company. Under the tide of "motor" are classed devices for driving a sewing machine by hand and foot power and engines to be attached to the machine and propelled by water, steam, air and electricity. The sewing-machines prior to Singer had no arrangement for applying power for driving them except the common hand-crank. This required the use of the right hand and only the left hand could be used for arranging and guiding the material to be sewed. The machines were put on a bench or table of home construction. Singer, in travelling about exhibiting his original machine, utilized the box in which it was packed for shipment as a table and conceived the idea of using a treadle similar to that employed on the old spinning-wheel and having a pitman attached to the handle on the driving-gear to assist him in working the machine. He used an ordinary door-hinge as a fulcrum for the treadle, which was longer than the depth of the box and projected therefrom. He therefore placed the hinge about where the instep of the foot would be and attached the other half of the hinge to the box and thus found that he had a rocking motion on the treadle that aided in securing uniform motion to the machine. He soon discovered that, with the addition of a balance-wheel on the upper shaft for increasing the momentum when the machine was once in motion, he could run it by foot-power with his rocking treadle, operated by heel-and-toe motion and so have the use of both hands for guiding and arranging the material. This was a great gain in utilizing the machine and he soon after produced an iron stand having a rocking treadle constructed for the use of both feet. Mr. Singer did not realize that he had made a great and important discovery and failed to apply for a patent. He was very much chagrined after having used the invention for two years and thus debarring himself from a patent, to be informed of his oversight by a rival manufacturer. Many devices have been made for driving the sewing-machine by foot-power since that time, the latest being the revolving treadle with the bicycle movement but none of them have been as good as the rocking treadle. Backus, in 1874, made a water-motor that had some sale; Ericsson made an air-engine in the same year and a number of small steam-engines and a great many devices using springs, weights, etc., have been tried, but no efficient motor has been successfully put on the market until the development of the use of electricity for power. The "Diehl electric sewing machine motor" can be directly connected to the main shaft of a sewing-machine and is a great success on account of its convenience, compactness and effectiveness. In its smallest form, for driving individual machines, the field-magnet is secured to the arm of the machine, the armature being carried inside a brass wheel which acts as a balance-wheel. The rheostat is attached to the ordinary foot-power table or cabinet case and is connected by a pitman with the treadle so that the machine may be started and stopped and the speed regulated as desired by pressing the foot on the treadle. The versatile inventor of this motor has made a notable demonstration of the uses of electricity by applying it to the operation of a sewing machine drop-cabinet and its contents for the purpose of public exhibition. The cabinet stood in a show-window on Broadway and, apparently of its own volition, the cover of the case opened, the sewing-machine was elevated from its receptacle under the table, the doors to this receptacle were folded back and the machine began operation at a high rate of speed. After a few minutes this operation ceased, the machine descended to its former position, the cabinet was fully closed and became an elegant and useful table, appropriate to the most ornate furnishings. For the factory operation of sewing machines there are ingenious devices for their stable support on tables which are made in sections, carrying the shafting and so arranged as to be readily connected in longer lengths as desired and adjustable to any unevenness of floor. These tables are made for the operation of one or of two rows of machines from one line of shafting, which is so carried beneath the tables that it is easily adjusted. The tables have a thick wooden top that may be entirely flat, or it can be provided with convenient work-holding troughs. In point of convenience, cleanliness, safety and economy these tables leave nothing to be desired, for they seem to satisfy all requirements in these respects. In the matter of power transmission from the shaft to the machine there are several devices to enable the instant stopping and starting of the machines. The use of electricity has demonstrated the feasibility of attaching the electric motor directly to a shaft for transmitting power at the point where it is needed. Much economy is gained by this method over the old system of successive countershafting and belting, with its dangers, its expense and the loss of efficiency. The ideal system will have been reached when the motor is attached to the head of each sewing machine, so that all objects intervening between the source and the subject of power, other than the wire for the electric current, can be dispensed with. The reports to "the sewing machine combination" of the sales of sewing machines during the four years 1873-76 show a total of 2.303.941, the average for each year being about 576.000. As these reports terminated with the year 1876, we have no other information as to the extent of sewing-machine manufacture since that time than what is indicated by the United States census reports of 1880 and 1890. The total value of production reported at the census of 1880 for one year was $13.863.188, the census of 1890 showing a value of $12.823.147. These figures indicate that the average number of machines made annually during the last twenty years has been from 500.000 to 600.000. A comparison of the census reports of 1880 and 1890 shows a decrease of fifty per cent, in the number of establishments engaged in the manufacture of sewing machines, but also shows that the number of persons employed was about the same and that their average wages increased about ten per cent, during the decade. In 1880 the average wages were $485 and in 1890 they were $567 per annum, thus showing the class of labor employed to be of a very high order. The reports, at the census of 1890, from fifty-six establishments showed the employment of 9.121 operatives, whose wages amounted to $5.170.555. The market value of their product was $12.823.147, so that the cost of their labor constituted forty per cent, of this value. The table on pp. 536 and 537, relating to exports of sewing machines, shows the value of such exports to have exceeded $67.000.000 during thirty years, 1865-95, the annual average during the last ten years exceeding $2.500.000. This sum does not, however, adequately represent the foreign use of the American sewing-machine, because American establishments are extensively engaged in the manufacture of these machines in other countries. An active foreign demand for the American sewing machine was developed during the Civil War, 1861-65 and the value of machines exported during the year ending June 30, 1865, was nearly $2.000.000. The foreign selling-price per machine was less than the domestic price, but the high premium on foreign exchange and the depreciated United States currency made the business fairly remunerative at that time. As previously stated, the cost of labor in the manufacture of a sewing machine is forty per cent, of its total cost at the present time but during the period from 1861 to 1865 wages did not increase as fast as the value of the currency decreased and thus the machine could be sold at a price in specie very much below its value in United States currency. Upon the gradual restoration of that currency to its normal specie value, however, the rates of wages were not reduced to correspond to their increased purchasing power; on the contrary, these rates have steadily increased, as has been shown. Thus the cost of the domestic manufacture became too high to enable competition in the world's markets with the numerous imitators who were manufacturing in Great Britain and on the continent of Europe. Therefore some of the American manufacturers established factories in foreign countries and supplied them with American machinery and tools for producing facsimiles of the machines made by these manufacturers in the United States. The "American system" of making all parts of the finished product completely interchangeable has been carried to its highest development in the manufacture of sewing machines, every piece being made to gauge and tested before assembling. In no branch of manufacture has the use of automatic machines and tools of fine precision become more essential than in this. The special tools required to make the various parts of some of the many varieties of sewing-machines often require greater inventive talent and ingenuity than that displayed in the machine produced.

The Singer Company have continued the manufacture in foreign countries of duplicates of the machines made in this country and the factories erected by this company at Kilbowie, near Glasgow, Scotland, are equal in capacity to the factories at Elizabethport, N. J. and have produced about 400.000 machines annually during the past four years. The total number of all the machines made by I. M. Singer & Company and their successors, The Singer Manufacturing Company, from 1853 to October 1, 1895, is 13.250.000 and of this number 5.877.000 have been made in factories located in foreign countries but under the direct control and management of the American company. The average value of the exports of sewing machines, including cabinet-work and parts of sewing-machines, from the United States, indicates that about 150.000 machines are exported annually and it is a fair estimate that the total number of American sewing machines sold annually in foreign countries, including those made abroad, is equal to the sales in the United States by all the American companies. The export of sewing-machine cabinet-work is a matter of considerable importance, because the United States easily surpasses all other countries in the wealth of its woods for this purpose, in the ingenuity of its cabinet-makers and in the efficiency of its woodworking machinery. The different climatic conditions of other countries and continents do not admit of finishing the woodwork in this country but it is cut "in shape" and exported "in the white", so that it can readily be put together and finished where it is to be used. The number of tables and cabinet-cases for footpower stands and of cases for hand-machines, exported by the Singer Company aggregate about 694.000 annually; of this number the cases for hand-machines constitute about seventeen per cent. The proportion of hand to foot-power machines used in Europe and in Asiatic countries is far greater than in the United States, where the operation of a sewing machine by hand is very exceptional and usually confined to those crippled and physically unable to apply foot-power. The great difference in social conditions is largely accountable for this peculiarity and the increased use of the hand-machine in Europe is also largely due to the itinerant character of the urban population, who find the tables and stands an impediment in their constant moving from house to house. The most remarkable industrial development in connection with the sewing machine has been its diversification and adaptation for use in a great variety of manufactures, which have thus been enabled to increase the quantity, quality and value of their product and to cheapen its cost to the consumer.

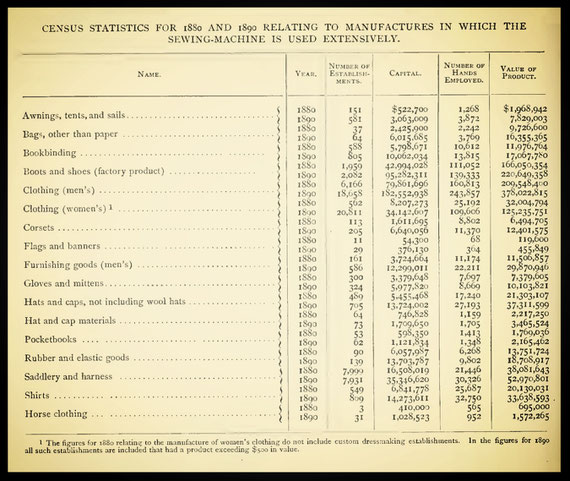

In the census reports relating to the principal manufacturing industries that use the sewing-machine introduced and demonstrated that neater and more uniform work could be done on the machine. The result was the concentration of the scattered home industry into convenient factories and the use of largely, the figures show that the total value of their steam-power for driving the machines. The products in 1890 had increased about seventy-five per cent, from 1880. These census figures are given in a tabular statement which is appended and which contains comparative data for seventeen classes of industry in the operation of which the sewing machine is an important factor. These industries employed 661.000 hands in 1890; they had about $437.000.000 invested in machinery, tools and implements of all kinds and the value of their product approximated one thousand million dollars ($1.161.196.659) of machines for stitching the uppers suggested the need of machines for sewing on the soles and in 1861 the machine known as the McKay, under patents to L. R. Blake and others, was first put into successful operation. The time and money put into experiments on this machine and the large amount of work which it performed, caused the owners of the patents to place a royalty on each pair of shoes sewed on it, as the only way to obtain a fair remuneration for their invention. The value of the invention to its owners may be estimated when it is stated.

In no branch of manufacture has a greater revolution occurred than in boots and shoes. The fitting of the uppers was formerly accomplished by sending them out in small quantities to be sewed and stitched by hand in the homes of the operators. The handworkers bought sewing-machines when they were that as many as 900 pairs of shoes have been sewed on one machine in one day of ten hours that the average license was at the rate of two cents per pair and that over 350.000.000 pairs of shoes had been made on it up to the year 1877 in the United States and probably an equal or greater number in Europe. The McKay machine made the chain-stitch with a waxed thread. The outer sole was stitched to the inner sole by removing the last and placing the shoe on an arm similar in its general appearance to the human arm, with elbow bent to hold up the hand and swing around on the shoulder-joint, so as to bring the needle and awl in the overhanging arm into position above the shoe, to take up the thread from a very ingeniously worked underneedle in the arm inside of the shoe. The awl also had a lateral movement and acted as a feed to move the shoe forward as each stitch was taken. This very useful and meritorious machine has been superseded to some extent by the Goodyear machine, which makes the lock-stitch with waxed threads and sews on the sole in the same manner that it is done by hand. In the Goodyear process the last is left in the shoe and the welt is sewed to the inner sole and upper by a machine making the chain-stitch, that not only does the sewing but also draws the upper tight on the last and greatly assists in "lasting" and giving proper shape to the shoe. The outer sole is then sewed to the welt in a manner that successfully imitates the very best of hand-work.

The Goodyear machines are sold on a royalty plan based on their production. The next sewing machine of great importance was for working buttonholes and was made under patents to Vogel, Humphrey and others.

After years of experimenting the Union Buttonhole Machine Company produced a machine that was a marvel in its line. It worked buttonholes that had the peculiar "purl " of the best handmade buttonholes, to which they were superior in strength and finish. The manufacture and sale of this machine was not profitable to the Union Buttonhole Machine Company and in 1867 it passed to the Singer Company and by that company was still further improved and became a great success, having a large sale in the United States and Europe.

The Reece buttonhole machine was brought out in 1880; it is a wonderful organization of machinery and has had a large sale on the royalty plan, making it very remunerative to the owners of the patents.

During the early years of the sewing-machine, its use by clothing manufacturers was confined to the production of the medium grades, the custom tailors showing a great prejudice against machine sewing. This prejudice gradually disappeared as it became apparent that seams made on the machine were equal to the best handwork and the sewing machine is now in general use for making the finest garments. The enormous increase during ten years in the factory production of clothing is remarkable and it may fairly be claimed that the development of this industry has been coincident with the invention of special appliances and attachments adapting the sewing-machine for factory operation in the performance of all stitching processes, including buttonhole and eyelet making, attaching buttons, staying seams, etc. The concentration of clothing manufacture into factory operation has effected greater economy in the marketing of the cloth, especially the cheaper fabrics, such as jeans, shirtings, denims, etc. These are now sent from the mills where they are woven directly to the manufacturers of clothing, shirts, overalls, etc., thus saving the cost of commissions and handling, formerly incurred through the wholesaler, the jobber and the retailer to the local tailor or housewife. Several hundred sewing machines are sometimes operated in a single power plant for the manufacture of clothing. By the use of improved methods for cutting to standard sizes in great variety, well-fitting garments are now as easily obtained in "ready-made" as in "custom" clothing. By the use of the sewing machine they are as well made and are furnished to the wearer for what the material formerly cost him. Economies of equal importance have been effected in many other industries in which the sewing machine is the principal element of productive force. While these industries have thus been enabled to more than double their output during the last decade, the population of the country has only increased about one quarter. It is evident, therefore, that the quantity of sewing done in the home has been greatly reduced and that domestic burdens have been correspondingly lessened; also that the cost to the consumer of the products of the sewing machine has been reduced, all of which may fairly be claimed as the results of inventive genius and executive ability in the field of sewing-machine manufacture, its development and improvement. In the preparation of this article the writer has received invaluable information and assistance from Mr. John F. Elliott, who has been intimately connected with the sewing machine industry in many capacities for nearly forty years and much credit must be awarded him for the research and investigation which have given this brief history whatever of value it may possess.

As reproduction of historical newspaper articles and/or historical sources and/or historical artifacts, this works may contain errors of spelling and/or missing words and/or missing pages and/or poor pictures, etc.